The Court should no longer allow the government to require that broadcasters air opposing views on public issues.

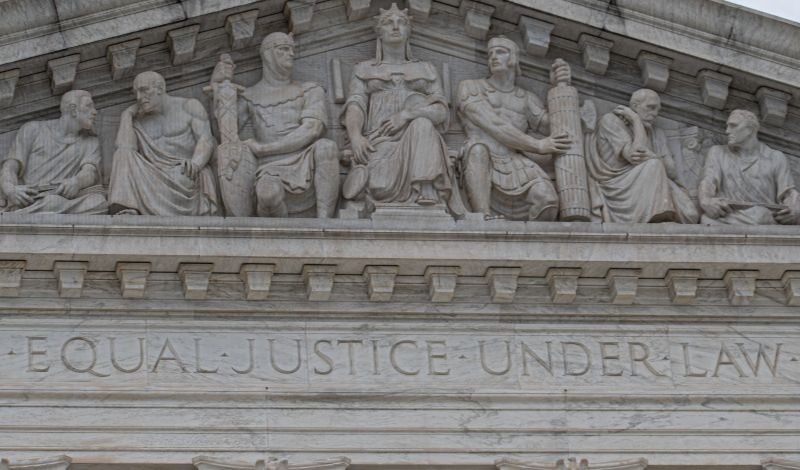

After a recent controversy over on-air remarks and threats of retaliation by the federal government against broadcasters, the debate over government control of broadcast content has resurfaced. Decades ago, in Red Lion Broadcasting v. Federal Communications Commission, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the since-abolished “fairness doctrine,” reasoning that broadcast scarcity justified limits on editorial discretion. New developments in U.S. media render the Court’s rationale obsolete—it should overrule Red Lion.

The fairness doctrine required every broadcaster to give “adequate coverage to public issues.” The coverage had to be “fair in that it accurately reflects the opposing views.” Broadcasters were required to provide opposing views at their own expense and on their own initiative. If a broadcaster aired an attack on a public figure, the broadcaster was required to give that person an opportunity to respond to the attack personally.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) enforced the doctrine primarily through the process of granting and denying licenses to broadcast over a specific radio frequency. The FCC is empowered to grant or deny licenses by applying two extraordinarily broad statutory standards—the “public interest” and the “public interest, convenience, or necessity.”

In Red Lion, the Court acknowledged that the fairness doctrine conferred on the federal government unprecedented power to regulate speech and the press. It held that the government could exercise that power because of a unique characteristic of the then-new mediums of communication. Radio and television frequencies are inherently scarce. Allowing broadcasts on overlapping frequencies would create cacophony. As a result, the government could grant licenses only to a few of the thousands of applicants who sought them.

When the government granted a license, it conferred a monopoly on a broadcaster. In that unique situation, the Court reasoned, the government had an obligation to further the values of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution by regulating the content of the broadcasts to ensure adequate, fair, and balanced coverage of all issues of public importance.

That reasoning process also supported the FCC’s statutory power to regulate mergers and acquisitions proposed by broadcast licensees. Given the extraordinary power of broadcasters, the FCC has a duty to ensure that this power is not concentrated in just a few hands. The FCC holds the power to approve or disapprove broadcaster-proposed mergers and acquisitions by applying the same extraordinarily broad statutory standards that it applies in granting or denying broadcast licenses: It asks whether a proposed merger would be in the public interest and would further the public convenience, interest, or necessity.

The communications environment has changed dramatically since the Court decided Red Lion. Broadcasting accounts for a small and diminishing proportion of the programming that people can access on radio and television. The overwhelming and growing proportion of what people watch on television is never broadcast over the scarce airwaves; it is provided by cable and by the internet from thousands of sources with widely varying points of view on every issue of public importance.

Famous podcasters such as Joe Rogan have far larger audiences and far more influence over issues of public importance than those who rely on a broadcast license for access to the public. Moreover, we can rely solely on the market to allocate scarce broadcast frequencies: Initial licenses can be auctioned, and existing licenses can be bought and sold.

The conditions that supported the Supreme Court’s decision in Red Lion have changed so completely that the government should have no power to regulate the content of broadcasters, whether through decisions to grant or deny licenses or through decisions to grant or deny proposed mergers and acquisitions. The Supreme Court should overrule Red Lion at its earliest opportunity.

There was no pressing need to revisit this area of law for many years. The FCC rescinded the fairness doctrine in 1987 during the Administration of President Ronald Reagan. The FCC now relies primarily on market forces, auctions and sales, to determine who can and cannot hold a broadcast license. Yet, the FCC still has the statutory power to grant or deny broadcast licenses and to grant or deny mergers and acquisitions proposed by broadcasters, limited only by the virtually meaningless and completely subjective statutory standards of public interest and public convenience, interest, or necessity.

The potential for abuse of those powers became apparent in the wake of the tragic assassination of Charlie Kirk, a highly successful public speaker who played an important role in helping President Donald J. Trump win the presidential election in 2024. When late-night comedian Jimmy Kimmel used the Kirk assassination as the point of entry for a joke about President Trump, FCC Chair Brendan Carr threatened to take regulatory actions against the broadcasters that aired the joke. Carr’s boss, President Trump, referred to the incident as a reminder of his power to take away the licenses of broadcasters that criticize him.

Two companies that have many broadcast licenses immediately responded by suspending indefinitely all broadcasts of Kimmel’s show. One of those companies had a controversial merger proposal before the FCC at the time, and the other regularly makes acquisitions that require FCC approval. They have since changed course and decided to broadcast Kimmel’s show.

As long as Red Lion remains the law, every President will have near-complete power to regulate the content of all broadcasters. The Court needs to correct that situation by overruling Red Lion at its earliest opportunity. Carr and President Trump are likely to provide that opportunity in the near future.