Experts point to the adverse effects of expanded mineral mining on and near tribal lands.

President Joseph R. Biden has pledged to cut U.S. greenhouse gas pollution in half by 2030. Six years remain for the United States to meet this lofty goal.

In a recent article, three legal experts argue that domestic emissions goals—which increase demand for clean energy generation and transportation—also increase demand for critical minerals. If the United States relies on new mining alone to meet this demand, these experts underscore the inevitable outsized environmental impact on Indigenous communities.

The transition from fossil fuels to clean energy generation and transportation requires heightened production of solar photovoltaic plants, electric vehicles (EV), batteries, and onshore wind plants. The critical minerals to produce these items—also known as energy transition minerals—are required in large quantities to replace existing fossil fuel based items. The International Energy Agency estimates, for example, that the average onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral inputs than a fossil fuel plant, and the average electric car requires six times more mineral inputs than a conventional gas-powered car.

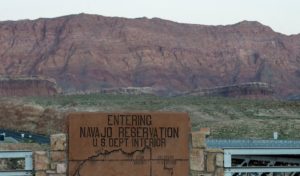

In their recent article, Laura Berglan, a senior attorney with the Tribal Partnership Program at Earthjustice, Blaine Miller-McFeeley, a senior legislative representative at Earthjustice, and Andrea Folds, a professor at Vermont Law School, note that a vast majority of untapped deposits of energy transition minerals in the United States are located within 35 miles of a Native American reservations. These deposits include 97 percent of the nickel deposits located in the United States, 79 percent of lithium, 68 percent of cobalt, and 89 percent of copper. Due to their proximity to these deposits, Native nations are—or will become—fenceline communities exposed to the brunt of environmental harms caused by domestic mining.

Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds highlight that most of these mineral deposits are not on reservations or trust lands, but instead are located within ancestral lands where tribes used to live and still retain cultural connections. Because tribes do not possess title to this land, though, they retain limited control over mining activities and remain exposed to the environmental harms of mining.

Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds contend that alternatives to new mining should be prioritized through expansion of the circular economy of minerals by recycling, reusing and substituting minerals whenever possible. They argue that the proper regulatory framework can facilitate the collection, transportation, and reuse of minerals—as well as create clean energy jobs in the recycling sector.

Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds detail the changes that would nudge the circular economy forward, including tax incentives and expansive labeling regulations that requires information on the amount and type of recycled material used. They also suggest implementing requirements that the producer of a technology take responsibility for the product throughout the supply chain—a model the European Union has implemented for EV batteries.

The demand for energy transition materials should be reduced in tandem with recycling and reuse policies, urge Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds. They contend that continued research support for material efficiency and substitution solutions paired with policies that reduce consumer demand—such as planning walkable communities or making public transit more accessible—will reduce the need for new mining projects and maximize the potential of the circular economy.

Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds also propose a holistic revamp of the existing hard rock mining laws and regulations. Mining in the United States is governed by the 1872 General Mining Act, which does not require mining companies to clean up toxic waste left behind from mining. This omission has led to an estimated 500,000 abandoned hard rock mines, which cause pollution that contaminates water, harms wildlife, and forever scars natural landscapes and sacred sites.

The General Mining Act does not require companies to compensate tax-payers by paying a royalty for harming public lands, nor does it give much discretion to land managers to deny proposed mines because mining remains the highest and best use of public lands.

Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds point to a variety of legislative reforms to remedy this imbalance, such as equalizing mining with other uses of public lands—such as hunting and recreation. Other proposals include raising royalty levels to the same percentage as oil and gas, establishing strong reclamation standards to restore abandoned mines and impacted areas, and prohibiting hard rock mining on protected lands.

In addition, the Bureau of Land Management and the United States Forest Service should update their regulations to include provisions protecting tribal communities and broaden the “unnecessary or undue degradation” standard, argue Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds.

They contend that tribes must be co-stewards of the land with the federal government and that agencies should adopt the principles of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC). FPIC would require consent from an impacted community prior to project approval, with the aim of reducing conflict and litigation. This would protect tribal communities while still enabling society’s green transition, according to Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds.

They also propose the adoption of higher labor and environmental standards for hard rock mining in the United States. They advocate the incorporation of these standards in enforceable trade agreements through official certifications such as the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA). Furthermore, the U.S. Department of Defense and the General Service Administration should wield their purchasing power to require suppliers to use IRMA-certified critical minerals, argue Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds.

Reforms that would reduce mining for critical minerals and require sustainable mining practices will diminish the outsized impact of the green transition on tribal communities, conclude Berglan, Miller-McFeeley, and Folds. They emphasize that a critical mineral supply chain should not be built “on the backs” of Native nations.