Commentator argues that failure to regulate risky lending could lead to mass defaults.

For most Americans, owning a car is a necessity. People rely on cars to get to work, take their children to school, and participate in their communities. Historically, cars represented economic success, but without swift intervention, cars—and the loans consumers take out to buy them—could trigger a major crisis for the U.S. economy.

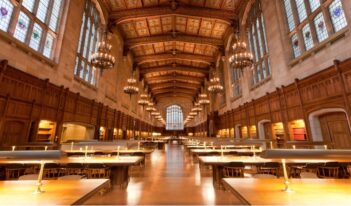

That is the argument law student Andrew Schmidt of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law makes in a recent article. He urges state officials, lawmakers, and regulators to intervene in the car credit market to curb lenders’ ability to issue subprime loans.

Since the Great Recession, the number of car loans issued in the United States has reached an all-time high. Alongside increased consumer demand, the rate of lending to people with low credit scores and high risks of default has also sharply increased. Often, lenders price cars as high as twice the Kelley Blue Book value, a practice that allows them to “profit from the down payment and origination fees alone.” The subprime loans they issue also carry exorbitant interest rates—sometimes exceeding 30 percent.

Consumers are already in dire financial straits when they are taking out a subprime loan—they are unable to qualify for a conventional car loan. With no bargaining power and the urgent need for a car, they have little choice beyond accepting the lender’s terms.

In addition to staggering loan terms, lenders also frequently turn to deceptive remedies for repossession, including luring borrowers back to dealerships on the promise of renegotiating or installing remote-controlled devices that prevent the car’s engine from restarting. By engaging in “self-help” repossession, lenders avoid hiring “repo men” to track down and recover cars, further protecting their profits. Because many borrowers default within a year, the cars to which the loans are secured barely depreciate, allowing lenders to resell them on similar terms.

Although lenders profit from defaults, some borrowers spend decades paying off a car they only drove for a few months. To recoup loan balances, lenders engage in aggressive collections tactics such as lawsuits and wage garnishment. Some subprime lenders have attorneys on staff to keep up with the rapid rates of default.

Schmidt worries that a mass series of defaults on auto loans would have “disastrous consequences” for the economy. Risky lending creates high demand for used cars, causing price inflation. Because lenders profit even when borrowers default, they have an incentive to originate loans that will likely default. As with the 2008 housing crisis, a systemic mass default scenario would result in a larger supply of repossessed cars. Used car prices would fall, followed by new car prices. As loan-to-value ratios increased, borrowers close to default would be unable to refinance, leading to another wave of repossessions and price decreases. Schmidt notes that an auto market crash would hit the poorest households hardest. For low-income Americans, having a car repossessed could mean forfeiting gainful employment, amassing crippling debt, and even losing eligibility for public benefits.

Subprime auto lending is not exempt from oversight by state and federal regulators, including members of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Federal Trade Commission. These agencies investigate and prosecute lenders for unfair, deceptive, and abusive tactics. Schmidt suggests that their efforts fall short, however, because the agencies’ actions only target unfair financing, debt collection, and repossession practices, rather than lenders’ disregard for borrowers’ ability to repay loans.

The CFPB appears reluctant to take on risky auto lenders. Out of 135 actions the board has taken, only 13 involved subprime auto lenders.

Citing the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) the CFPB has determined that a payday lender’s failure to consider ability to repay was abusive under the statute, but the agency has not yet imposed this standard on auto lenders. Relying on the precedent applied to payday lenders, Schmidt explores the feasibility of issuing an “ability-to-repay rule” modeled on the one that applies to mortgages. The rule would require lenders to vet borrowers using verifiable information like paystubs and tax records. Loans issued in compliance with the rule would carry a rebuttable presumption of validity. Under this scheme, private market actors would be entitled to sue lenders and pursue civil remedies such as contract rescission and restitution.

Schmidt warns that the flipside of curbing lending is withholding credit from consumers who rely on cars to participate in the economy. Specifically, economists who have studied the impact of the mortgage ability-to-pay rule argue that the tighter underwriting standards disproportionately impact African-American and Latino borrowers, as well as borrowers living in low-income communities. Virtually all borrowers with FICO scores below 660 are barred from the mortgage market. Subprime auto loan borrowers’ credit scores are often lower than that by 100 points or more.

Instituting an ability-to-repay rule could exclude entire communities from buying cars on credit too. The consequences are especially stark in the auto industry, which does not offer lower-cost alternatives like rental housing. Schmidt acknowledges that “limiting subprime borrowing in the housing market may prevent individuals and families from building intergenerational wealth through homeownership.” But he observes that “the impact of limiting car credit could be more immediate and devastating for many low-income people.”

To avoid barring entire communities from car ownership, Schmidt advocates for an aggressive enforcement approach that would stem the tide of subprime loans without cutting off access to credit. Unlike a new rule, which could take a year or more to be implemented, agencies could immediately ramp up enforcement under existing laws like Dodd-Frank. Enforcement is also discretionary and flexible, allowing regulators to adjust their response to a specific case. Regulators would have to apply rules uniformly, which would prohibit them from adjusting their response when necessary. In addition, Schmidt touts the lack of a private right of action as a benefit to enforcement. He argues that limiting liability for lenders will encourage them to continue extending credit, even under heightened government scrutiny.

Without meaningful intervention, the subprime auto loan bubble is primed to burst, Schmidt warns. Regulators can glean valuable insight from the 2008 housing crisis, but because most car ownership requires extending credit, remedies such as the ability-to-repay rule cannot be easily implemented. Instead, Schmidt calls upon agencies to ramp up enforcement efforts against the most abusive lenders without cutting millions of consumers off from private transportation.