The FCC’s authority to regulate needs to reflect the modern realities of broadcasting.

The George Washington University Law School’s Richard J. Pierce, Jr., is not only a distinguished scholar but also a long-time friend and colleague. So, I read his recent essay with great interest.

Pierce’s bottom-line conclusion is that the U.S. Supreme Court needs to overrule its 1969 decision in Red Lion Broadcasting v. Federal Communications Commission. In that landmark decision, the Court upheld the constitutionality of the “fairness doctrine” adopted by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which required broadcasters to cover issues of public importance in a balanced way. The Court rejected the claim that government regulation of broadcast content—which the fairness doctrine intrinsically required—infringed on broadcasters’ free speech rights under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. For First Amendment purposes, the Court distinguished broadcasters from the print media and other speech platforms on the basis that broadcasters’ use of radio spectrum frequencies is a scarce public resource.

Pierce argues that “new developments in U.S. media render the Court’s rationale obsolete—it should overrule Red Lion.” I agree completely. Indeed, in an article published in 2009, I argued that it was past time for the Supreme Court to jettison its analog-age precedents, including Red Lion, that accord broadcasters less First Amendment protection than all other media. Justice Clarence Thomas cited my article approvingly in a concurring opinion, calling on the Court to revisit its precedents allowing government regulation of broadcasters’ programming content.

Although the Supreme Court has yet to do so, it might ultimately adopt my view—and Justice Thomas’s and Pierce’s—if presented with an appropriate opportunity.

But while waiting for the Court to overrule Red Lion, there is another route to constrain FCC regulation of broadcast content that arguably infringes broadcasters’ First Amendment rights. The U.S. Congress should eliminate the FCC’s “public interest” authority from the Federal Communications Act because the media marketplace has dramatically changed, and now provides, as Pierce explains, “thousands of sources with widely varying points of view.” The broad delegation to the FCC of essentially indeterminate authority to act in the “public interest” has been used over the decades to justify the government’s regulation of programming content. I have argued that this “standardless standard” is unconstitutional.

Recall that the fairness doctrine, which the FCC stopped enforcing in the 1980s and removed from its regulations in 2011, was grounded in the Communications Act’s “public interest” delegation. And relevant to the conflict between FCC chair Brendan Carr and Jimmy Kimmel referenced by Pierce, the FCC must determine that any proposed transaction involving the acquisition or transfer of broadcast licenses is “in the public interest.”

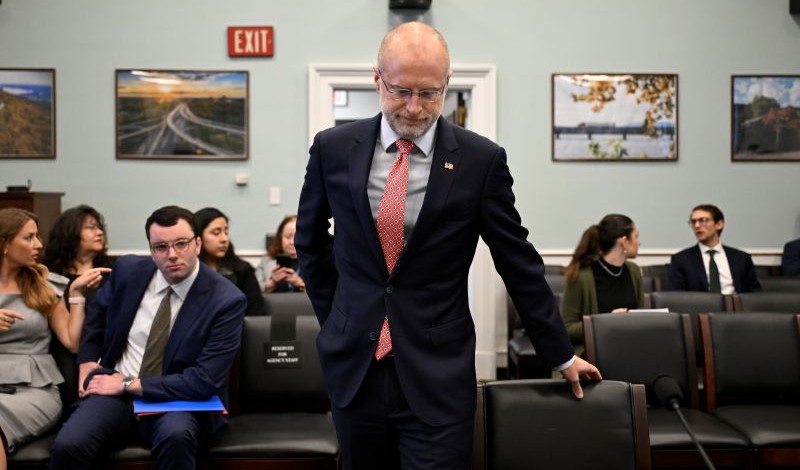

It is this public interest hook that gives the FCC leverage that can be used to threaten a broadcaster’s free speech rights. And this is what Carr is accused of doing—threatening to hold up FCC approval of a proposed transaction involving the transfer of broadcast licenses if Nexstar did not take Jimmy Kimmel’s show off the air. I recently said I did not like Carr’s veiled threats invoking the FCC’s public interest authority, but I also stated there is a history of Democratic-led FCCs doing the same. Indeed, Democratic FCC chair Newton Minow, in his famous 1961 speech decrying television programming as a “vast wasteland,” warned broadcasters that “there is nothing permanent or sacred about a broadcast license.” In other words, FCC commissioners from both political parties have invoked the public interest standard to threaten free speech rights.

Congress should recognize that, given the indisputably dramatic marketplace changes in the media and telecommunications environment, the Communications Act is due for a substantial—I would say radical— overhaul. An essential element of that overhaul should be the elimination of the FCC’s indeterminate public interest authority, which, from the agency’s inception to the present, has undergirded its regulation of programming content. This was true in Red Lion, and it remains true today.

I will concede that I am not optimistic that Congress will act anytime soon to do what I suggest here and have long recommended. But it could, and it should.

Meanwhile, along with Pierce, I would be happy for the Supreme Court to be the first mover.

This essay is part of a series, titled “Revisiting Broadcast Fairness.”