Experts explore the impact of concussion legislation on adolescent health and education.

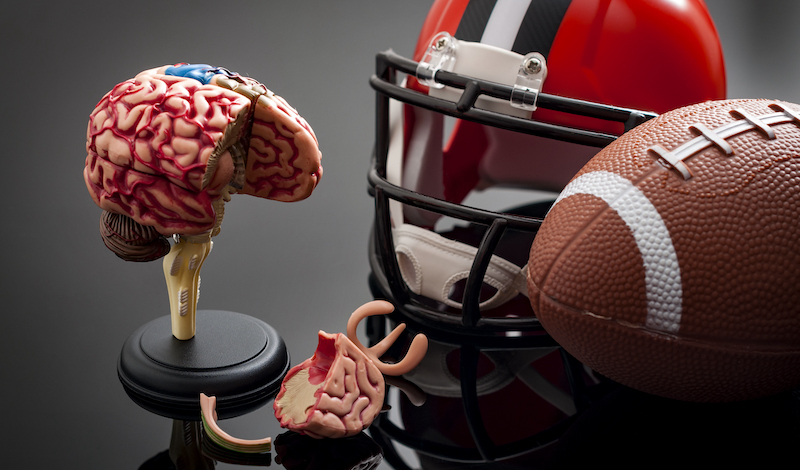

Should parents and guardians let their children play youth sports? As many as 1.9 million children suffer a sports-related concussion each year, posing long-term risks to young developing brains. Meanwhile, Will Smith’s performance in Concussion and a string of Pop Warner youth football lawsuits have brought youth concussion prevention into the spotlight.

Over the past decade, public health scholars, lawyers, and policymakers have debated the effectiveness of concussion legislation and considered potential reforms to combat the ongoing health impacts of youth concussions.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched a series of educational initiatives in 2003 called HEADS UP aimed at raising awareness about concussion prevention, recognition, and response. The lack of federal legislation for youth concussions, however, led many states to enact their own regulatory schemes.

Washington passed the first state concussion law in 2009. Named after Zackery Lystedt, who suffered a catastrophic brain injury after hitting his head during a middle school football game, the law required that youth athletes suspected of sustaining a concussion receive approval from a licensed health care provider before returning to play. The law also mandated that schools implement educational programs to inform coaches, parents, and student athletes about the nature and risks of concussions.

Between 2009 and 2014, all 50 states enacted youth concussion legislation, which has been shown to increase concussion reporting, improve education for coaches, and decrease recurrent concussion rates. Some states have added more stringent requirements concerning minimum time out before returning to play. For instance, New York prohibits return to play until student athletes are symptom-free for at least 24 hours, whereas California requires a graduated return to play of at least seven days under the supervision of a licensed health care provider. Fourteen states not only restrict return to play but also return to the classroom.

Despite existing legislation, concussion injuries and sports litigation persist. State lawmakers remain concerned about the effectiveness of implementation strategies, gaps in education, and expansiveness of coverage. International experts in brain trauma research have also called for youth sports reform to prevent repetitive head impacts under the age of 14. Above all, parents fear the potential consequences of allowing their children to play football or other contact sports.

In this week’s Saturday Seminar, scholars debate whether current concussion legislation provides sufficient safeguards for youth sports.

- Although every U.S. state legislature has passed a concussion law targeted toward youth sports, the effectiveness of these laws and the best means of implementing them remain unclear, explains Francis X. Shen of the Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics in an article published in the Duquesne Law Review. Shen found that youth concussion laws have received “widespread acceptance,” but third parties may be resistant to specific concussion mandates when these protocols interfere with athletic aspirations or individual medical relationships. Nevertheless, Shen concludes that these laws have increased accurate recognition and reporting of concussions. Thus, Shen argues, regulators should increase dissemination of concussion information to provide student athletes and their parents with a better assessment of the risks.

- In an article published in the Journal of Business & Technology Law, Kerri McGowan Lowrey of the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law investigates the current sphere of statewide legislation surrounding concussions in youth sports. According to Lowrey, many states initially adopted similar frameworks to Washington state’s Lystedt Law, but actual applications of these laws differed widely between states. For example, Washington’s law requires education of concussion risks, but what constitutes said “education” varies, and can therefore fluctuate in effectiveness. Recently, states have begun to clarify and strengthen their statutes in line with medical guidance. Lowrey also notes that some regulations may improve the safety of recreational sports overall by mandating proper use of sports equipment, such as helmets and mouthguards.

- In an article published in the Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics, Sydney Diekmann, a senior health care consultant, and several coauthors argue that mandated concussion education for coaches and student athletes will not produce beneficial health outcomes. The Diekmann team explains that although states’ education-based interventions can produce short-term increases in relevant knowledge, this knowledge does not lead to behavioral changes that successfully decrease the risks of concussions. Thus, the Diekmann team concludes that concussion interventions focused on primary prevention and changes in concussion reporting will be more effective.

- In an article published in the Catholic University Law Review, Tracey B. Carter of the Belmont University College of Law considers whether and how state youth concussion laws promote culture changes in youth and professional sports. Although private individuals have turned to the courts to address the concussion issue in recent years, Carter posits that litigation is not the most effective remedy. Carter argues that states should continuously update their concussion laws in light of new research, implementation issues, and best practices. Carter also contends that youth sports governing bodies, such as Pop Warner, can play a significant role in reexamining local safety practices and protocols.

- The variation in concussion legislation across the United States shows discrepancies in protection for youth playing sports, argues Kelly L. Potteiger and several coauthors in an article published in The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. Although all 50 states have legislation concerning sports concussions, barely a third of the statutes encompass public, private, and youth sports organizations. Similarly, other statutes only protect students that fall within a certain age range. The Potteiger team contends that concussion legislation should include all children, regardless of age or involvement in sports, to ensure consistency in rights. In addition, health care providers should play a greater role in developing such policies, particularly those geared toward concussion education.

- In an article published in Sports Health, Andrew W. Albano of the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville and several coauthors provide a medical-legal analysis of concussion care. An athletic coach has a duty to act as a physician when undertaking a concussion evaluation, or else they risk a charge of gross negligence, argue the Albano team. Moreover, if a licensed health care provider is unavailable to evaluate a suspected concussion, then the student athlete cannot return to play under current concussion legislation. Albano and his coauthors, however, identify various barriers to effective implementation of these legal mandates, including parent cooperation and access to concussion management providers in rural and underserved areas.

The Saturday Seminar is a weekly feature that aims to put into written form the kind of content that would be conveyed in a live seminar involving regulatory experts. Each week, The Regulatory Review publishes a brief overview of a selected regulatory topic and then distills recent research and scholarly writing on that topic.