Scholars analyze linguistic and cultural barriers asylum-seekers face in the credible fear interview process.

Although most asylum seekers in the United States are not ultimately successful, most succeed in interviews that establish they have a “credible fear” of persecution in their home countries and allow them to pursue their claim for asylum while remaining in the U.S. And for the minority of asylum seekers who fail these interviews, their failure may not be because they lack the requisite “credible fear,” but because their fate turns on a series of specific questions and terminology obscured in translation.

In a forthcoming article, law professors Kif Augustine-Adams and D. Carolina Núñez raise serious concerns about the U.S. asylum system because too many Spanish-speaking asylum seekers face serious linguistic and cultural barriers in their all-important “credible fear” interview with an immigration official.

Under U.S. immigration law, if noncitizens express a fear of return to their home country, immigration officials must refer their case to an asylum officer. By regulation, trained asylum officers within U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) must “elicit all relevant and useful information” in a “nonadversarial manner” to determine whether noncitizens have a “credible fear” of persecution on the basis of one of five designated categories. A positive determination may lead to release from detention and allows noncitizens to formally pursue an asylum claim in immigration court, but a negative determination results in near-immediate deportation.

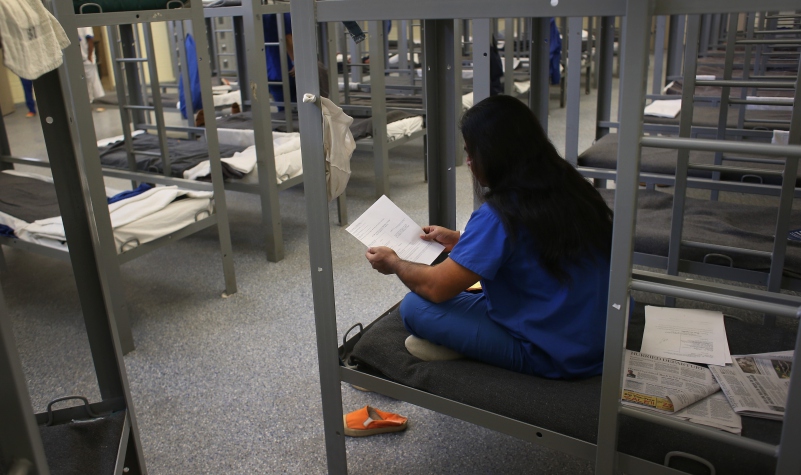

Given the high stakes involved in the credible fear process, nonprofit groups such as Proyecto Dilley organize teams of bilingual legal volunteers to prepare detained asylum seekers for their interviews. Augstine-Adams and Núñez spent eight weeks with one such organization assisting Spanish-speaking asylum seekers in a southern Texas detention center, where they identified two sites of potential “(mis)translation and (mis)interpretation” in the credible fear interview process.

The first site of confusion is the term “credible fear” itself. Augustine-Adams and Núñez observe that even in American English, before translating the term into Spanish, the meaning of “credible fear” is ambiguous—it is a technical term used exclusively in U.S. asylum law. Although a regulation defines “credible fear” as a “significant possibility” that a noncitizen can establish asylum eligibility, what constitutes a “significant possibility” remains hotly contested. The only federal court to interpret the phrase concluded that it means “a fraction of ten percent”—an extremely low bar. Recent USCIS interpretations, however, appear to embrace a higher, more exacting standard.

To compound the confusion, the Spanish translation of “credible fear” that is used in immigration agency documents and interviews—temor creíble—is a term that is “practically nonexistent in ordinary Spanish usage.” Augustine-Adams and Núñez analyzed Spanish linguistic databases and found that although hits on the term have increased in recent years, it remains an “extremely low frequency term.” As a result, those migrants whose fates are most affected by the ambiguous definition of this term are probably the least likely to comprehend its significance.

As another wrinkle, Augustine-Adams and Núñez found the specific word temor has a different meaning than the English term “fear,” especially in the countries from which many asylum seekers flee. The word “fear” most often refers to a concrete threat, such as death, failure, or heights, whereas the Spanish term temor is used in a way that suggests reverence or respect. In fact, Augustine-Adams and Núñez identified that temor is most frequently paired with Dios—the Spanish word for God. When Spanish-speaking asylum seekers are asked about their temor, it may not be clear they are being asked to describe a source of persecution.

But the definition of “credible fear” is not the only source of confusion created by the credible fear interview process. Augustine-Adams and Núñez argue that a second source of confusion occurs when asylum seekers must neatly fit intimate and often traumatic details of their lives into one of five stringently defined categories of asylum eligibility—race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. With the exception of the religion category, which is similarly understood in both English and Spanish, the four other categories pose significant interpretive challenges.

For example, the term “race,” even when translated, does not carry the same weight in the home countries of many asylum seekers as it does in the United States. When asked about her race, one detained asylum seeker said, “Yes, we are Indigenous. We are Hondurans.” For her, “race” and “nationality” were indistinct. But under the law, that distinction is critical. Persecution for being Indigenous may be sufficient for a positive credible fear determination, but persecution for being Honduran is not.

Augustine-Adams and Núñez observed a similar rift in translation when interviewers ask asylum seekers about their political opinions. For example, one asylum seeker in their study described her active opposition to the construction of a dam on a river in her home country, an activity which, under U.S. asylum law, fits cleanly within the political opinion category of eligibility. This asylum seeker, however, considered her activism personal, not an expression of her “political opinion.” After all, her organizing did not involve political parties or elections.

These sources of miscommunication can present grave consequences for asylum seekers who must often navigate the credible fear process in faraway detention centers without legal representation. Although bilingual legal volunteers can help clarify the various legal, linguistic, and cultural complexities, the difficulty of conveying the full meaning of key technical terms presents fundamental barriers that may undermine asylum seekers’ chances of success in their credible fear interview.

Augustine-Adams and Núñez’s findings also raise serious concerns about the broader U.S. asylum system. The credible fear interview process was originally meant to provide a layer of protection for immigrants fleeing persecution—but whether this process can still adequately fulfill its role is an open question in light Augustine-Adams and Núñez’s research. If U.S. immigration authorities turn away asylum seekers not because they lack a “credible fear” of persecution but instead because of a basic misunderstanding, policymakers may need to reform the asylum interview process to give adequate due process to those fleeing danger in their home countries.