The United States might well have saved many lives by following New Zealand’s science-based playbook.

COVID-19 is, in a sense, the ultimate final exam in administrative law and governance. Faced with a global pandemic threat, every government on the planet faces essentially the same public health challenge: to protect its people from a deadly contagious disease by regulating private and public conduct to minimize disease transmission—at a manageable cost to the economy. Countries’ performance in meeting that test can be measured in brutally objective terms: cases of disease and death, lost jobs, lost gross domestic product, and lost social cohesion.

By virtually any measure, New Zealand’s government has passed its COVID-19 test with high honors. COVID-19 came to New Zealand shortly before February 28, 2020, in the middle of its summer tourism season. With China and Europe traditionally accounting for a large share of New Zealand’s summer influx of visitors, COVID-19 could have spelled disaster for this island country. Once community transmission of the virus was established in New Zealand, as indeed occurred, epidemiological models suggested that a traditional “curve-flattening” response might have produced upwards of 14,000 deaths from COVID-19 in New Zealand (equivalent as a percentage of national population to 966,000 American deaths).

Rather than settle for traditional mitigation strategies, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, with the full support of New Zealand’s business community, adopted an aggressive strategy aimed at eliminating the virus.

The approach appears to have succeeded. Today, media outlets are reporting that New Zealand has not experienced a new case of COVID-19 for seventeen days. The last known case of COVID-19 in New Zealand has recovered, and all domestic restrictions on personal and economic activity are now lifted. New Zealand’s border remains closed to all but returning residents, who must quarantine upon arrival, but the virus has—for now—been eliminated from New Zealand. The cumulative toll of confirmed and probable number of cases in New Zealand over the four month period from the onset of the virus to its elimination stands at 1,504 cases with only 22 deaths (equivalent in percentage-of-population terms to 103,776 American cases with 1,518 deaths).

The United States, by contrast, has pursued a very different path with very different results. The United States has reported nearly 2 million U.S. COVID-19 cases and over 110,000 deaths, as of June 8, with tens of thousands of new cases and between 500 and 1,500 new deaths reported every day.

This essay examines the key elements of New Zealand’s successful COVID-19 strategy, as contrasted with the familiar and less successful response of the United States.

It will show that with one famous exception—discussed below—New Zealand’s battle to contain the virus followed the classic pattern ordained by the science of virus transmission: stopping the influx of the virus from arriving travelers; procuring personal protective equipment to protect essential workers; testing, contact tracing, and isolating those who test positive; and, most of all, mobilizing the public to lockdown and socially distance so as to slow or break the chain of transmission. The United States deviated from this pattern at every turn.

Travel restrictions. New Zealand’s pandemic response began inauspiciously. Two days after the World Health Organization declared the virus a “public health emergency of international concern,” New Zealand responded by banning the entry of airline passengers who had originated or traveled through China during a 14-day period prior to arrival. Inbound flights were allowed to continue from everywhere else, however, allowing both New Zealand residents and travelers from other countries to enter provided only that they agreed to self-isolate for 14 days.

Not until April 9 did the New Zealand Minister of Health issue an order requiring all airline or marine passengers entering New Zealand from overseas to undergo medical testing and quarantine in a supervised quarantine facility. With that step, the government stopped the foreign influx of the virus into New Zealand. But by then, officials had confirmed more than 1,200 cases in New Zealand and community transmission had been established.

The United States followed a similar trajectory with its travel restrictions from China. The United States, however, has never implemented a comprehensive ban on inbound travelers from overseas. And it still has not implemented a comprehensive test and quarantine requirement for travelers entering the country.

Personal Protective Equipment. While President Donald J. Trump failed to mobilize domestic production of personal protective equipment other than ventilators for COVID-19 patients on death’s door, New Zealand promptly created a live national register for personal protective equipment to identify Kiwi manufacturers that could assist in the fight against COVID-19 by manufacturing all types of equipment. Local businesses responded by ramping up domestic production or working with affiliates in China to source large additional purchases of masks, sterilized gowns, hand sanitizer, and face shields.

Testing. While the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was struggling to make its own coronavirus test work, the New Zealand government quickly organized a public-private consortium to procure test kits and reagents from other suppliers in a global scramble for scarce supplies. By mid-May, New Zealand had administered more than 100,000 coronavirus tests, yielding a rate of about 2,200 tests per 100,000 people—a much higher testing rate than either South Korea or the United States achieved over the same period.

Contact tracing. Once a patient has tested positive, standard COVID-19 pandemic protocols require a concerted effort to identify and test all the persons with whom that patient has had close contact over the past 14 days. New Zealand accomplished this through both low-tech and high-tech methods. The primary tracing tool was the Ministry of Health’s low-tech method, whereby officials interviewed each patient who tested positive for the virus to determine whom they had interacted with in the past 14 days. The national government later created a COVID-19 tracing cell phone application to help individuals retrace their steps when a contact tracer informs them that they have the virus. By contrast, the United States overall does not have any similar low-tech or high-tech tracing process in place, although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued guidelines for state contact tracing programs.

Lockdown. Perhaps the most difficult challenge for a government responding to a novel pandemic threat is that of mobilizing the population to take the threat seriously and change its normal behavior, drastically and immediately, to break the chain of virus transmission. This is the step at which New Zealand’s government has made history, by eschewing incremental mitigation strategies and immediately adopting very strong restrictions in an effort to eliminate, not just mitigate, community transmission of the virus.

On March 25, New Zealand implemented a nationwide lockdown, just three days after officials confirmed community transmission in New Zealand, with only 102 cases on the books. Moreover, New Zealand’s lockdown was strict—one of the strictest in the world. The government ordered all schools, public venues, and non-essential businesses—including restaurants and carry-out services—to close. The government prohibited public and private gatherings outside the residential bubble and instructed residents to stay at home, with an exception for “essential personal movement,” such as buying groceries or essential medicines. Government restrictions also prohibited residents from engaging in recreational activities outside the home except in isolation or with others in one’s own residential “bubble.” As Prime Minister Ardern stated in her March 23 speech, New Zealanders were “moving into self-isolation as a nation.” Although the lockdown was draconian, the Prime Minister offered her citizens the hope, if not the promise, that the lockdown also would be short—approximately four weeks—if they complied with the strictures; longer if they failed to comply.

Although New Zealand’s restrictions appear to have elicited a high level of voluntary compliance, police encouraged citizens to report violations and many citizens did so, producing more than 336 prosecutions over the space of a few weeks (equivalent on a population-adjusted basis to more than 23,000 prosecutions in the United States).

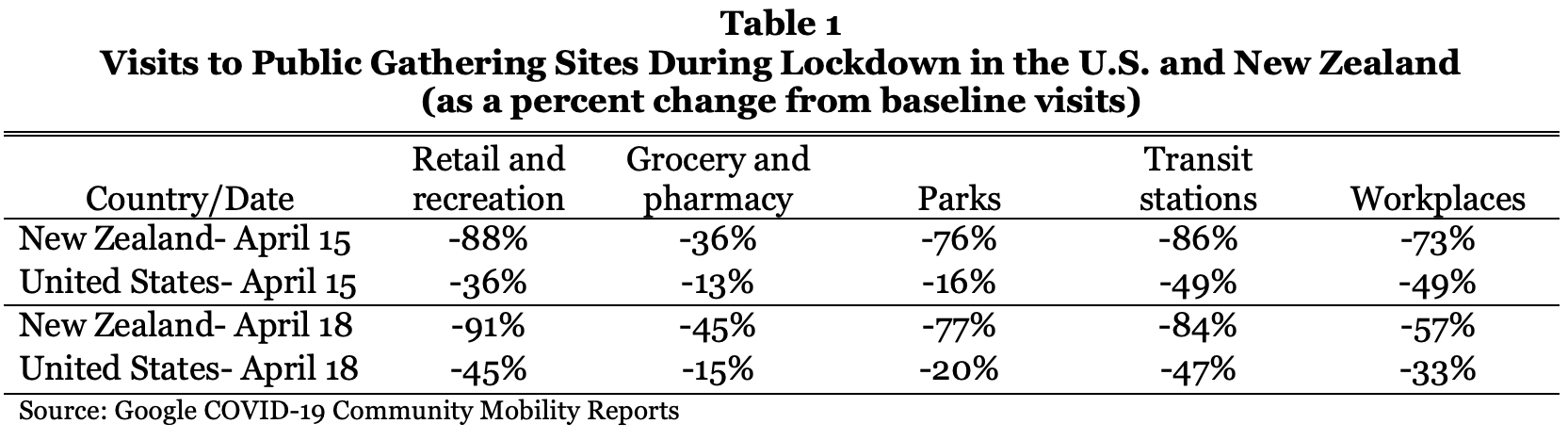

The combination of nationwide, mandatory, and enforced restrictions—framed by Prime Minister Ardern’s appeals to a shared sense of civic purpose and the promise of a short duration—appears to have achieved broad public support and a remarkably high level of overall compliance in New Zealand. Google Mobility Data anonymously collects and aggregates location data from people’s cell phones for periods before and after social distancing orders in countries around the world. Table 1 captures the reports of visits to public gathering sites for two sample dates (April 15 and April 18) occurring in the middle of the U.S. and New Zealand lockdown periods as compared to the pre-COVID-19 baseline.

Clearly, New Zealand’s restrictions produced a much larger change in the movement patterns of the citizenry on these sample dates than the various states in the United States have achieved by their piecemeal and decentralized strictures.

New Zealand’s reopening. New Zealand’s decision to lock down hard, early, and nationally came at a time when new case counts were doubling daily in New Zealand. As we have seen, Prime Minister Ardern offered her country the hope that a strong and early response would enable the lockdown to be short (about a month), and events confirmed the wisdom of her decision. After continuing to rise for twelve more days after the lockdown, New Zealand’s new case count then began to drop precipitously, from 89 cases per day on April 5 (equivalent in percentage of population terms to 6,100 new U.S. cases per day) to only nine per day on April 19. On April 27, the government began to ease the lockdown, albeit with major distancing restrictions in place. Officials further reduced restrictions on May 13, when the new case count reached zero, and lifted them entirely on June 8 with the recovery of the last known COVID-19 patient in New Zealand. All told, New Zealand’s nationwide lockdown lasted 26 days for the severe phase and 51 days for the severe and moderate phases combined.

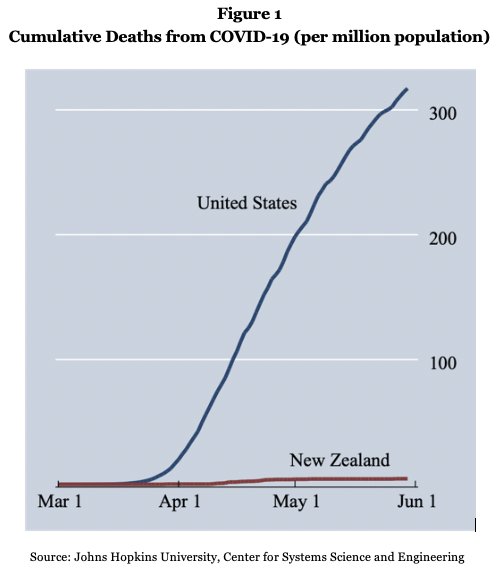

Clearly, New Zealand and the United States have chosen contrasting administrative approaches to managing the pandemic threat. New Zealand adopted a strong, science-driven, proactive, and centrally planned response, and executed it well. By contrast, the United States adopted a weak, incremental, and decentralized response, relying mostly on states, localities, and market actors to respond to the pandemic. The main consequence of these fateful choices is captured in Figure 1. To date, more than 110,000 Americans have died from COVID-19, with economic costs exceeding $3 trillion and no end in sight. New Zealanders, on the other hand, have experienced only about 1,500 cases and 22 deaths (the equivalent in population percentage terms to about 1,400 Americans). Although the crisis in America continues, the crisis in New Zealand is over.

To date, more than 110,000 Americans have died from COVID-19, with economic costs exceeding $3 trillion and no end in sight. New Zealanders, on the other hand, have experienced only about 1,500 cases and 22 deaths (the equivalent in population percentage terms to about 1,400 Americans). Although the crisis in America continues, the crisis in New Zealand is over.

Although some observers have dismissed New Zealand’s experience as the isolated achievement of a small, rural, island nation, the evidence suggests otherwise. The novel coronavirus spread around the world largely by air and sea travel, not land, making New Zealand’s island status irrelevant. Although it is true that New Zealand is less densely populated than the United States, New Zealand does have large population centers, and (as seen above) epidemiological models forecast a death toll of over 14,000 in New Zealand from a traditional, incremental pandemic response. In fact, the size and density distinctions may cut the other way. The larger and denser population of the United States logically suggests that a strict, early, nationwide, and mandatory approach might be more essential to success in the United States than in New Zealand.

In sum, New Zealand’s strategy confirms that an elimination strategy—involving nationwide, mandatory, and short-lived but strict mobility restrictions—can work if it is communicated well to the public, and backed by strong inbound foreign travel restrictions as well as abundant testing and tracing practices. The disparity between the effects of COVID-19 on the United States and New Zealand raises the question of how many lives would have been saved had the United States adopted New Zealand’s pandemic response strategy and implemented it with equal skill and resolve. Going forward, New Zealand’s strategy offers useful guidance to planners for how to respond to future pandemics in all countries.

The author would like to thank Libby Reinish, Demery Ormrod, Lauren Moscato, the reference librarians of UCONN School of Law, and Matthew Hall for valuable research assistance.

This essay is part of an ongoing series, entitled Comparing Nations’ Responses to COVID-19.