Scholars discuss the evolving legal landscape surrounding immigration detention centers.

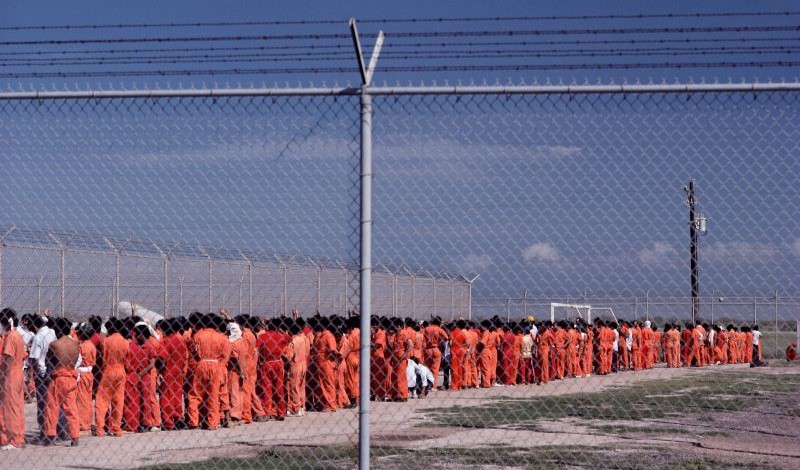

The United States operates the largest immigrant detention system in the world. A record-breaking 60,000 immigrants are currently detained in U.S. facilities. The recent opening of the largest U.S. federal migrant detention center on a military base indicates the intent of the Trump Administration to increase its detention figures through aggressive tactics such as workplace raids and courthouse arrests.

At the same time, advocates warn that the conditions in U.S. immigration detention centers have become increasingly dire. Rounded up through workplace raids and arrests at immigration courts, the number of immigrants in government custody is rapidly exceeding U.S. institutional capacity. Detainees, lawyers, family members, and lawmakers report overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and inadequate food, with at least 10 immigrants dying in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody since the beginning of 2025.

The Trump Administration’s aggressive detention tactics have met significant pushback: a federal judge temporarily halted new construction of “Alligator Alcatraz,” an immigration detention facility in Florida, and a New York federal judge ordered the Trump Administration to remedy conditions in New York City migrant holding cells.

Immigration detention is governed by a complex patchwork of federal statutes and regulations, such as the Immigration and Nationality Act, which grants the U.S. government broad detention authority. The Department of Homeland Security and its component, ICE, are primarily responsible for implementing and enforcing these regulations. Yet, the rapid evolution of policy directives, coupled with the distinctive characteristics of detained immigration courts have led legal experts to question the legality of the federal government’s mandate over the detention of immigrants.

The ongoing debate over immigration detention policy raises the fundamental issue of due process as it applies to noncitizens in immigration courts. Although the American Bar Association recently urged the federal government to ensure that immigrants receive due process, lawyers, advocates, and policymakers disagree over how to balance national security and border management with the constitutional and human rights protections owed to noncitizens.

In this week’s Saturday Seminar, scholars discuss the evolving legal landscape surrounding immigration detention centers.

- In an article in the Stanford Law Review, Paulina Arnold of the University of Michigan Law School traces how U.S. immigration detention became an exceptional regulatory carveout from ordinary civil confinement rules. Arnold claims that immigration detention’s lack of bond hearings and due process is a modern invention rather than a historical norm. Arnold explains that immigration detention was once part of a broad civil confinement system with few constitutional limits, but a mid-20th-century pause in immigration detention spared it from later judicial reforms, leaving courts to rely on outdated precedent. Arnold argues that this history undercuts jurisprudence that defends immigration detention as exceptional and bolsters calls to align detention policy with constitutional safeguards.

- In an article in the Georgetown Immigration Law Journal, Azadeh Shahshahani of Project South and Kyleen Burke of Suffolk County Legal Aid Society, argue that U.S. immigration detention centers exploit detainees through work programs, coercing labor for pennies an hour in violation of international prohibitions on forced labor. Although challenges to these practices are often brought under federal law, Shahshahani and Burke note, parties could benefit from invoking international law, particularly treaties ratified by the U.S. Shahshahani and Burke explain that these treaties prohibit civil detention centers from engaging in forced labor and other internationally condemned practices. Shahshahani and Burke contend that incorporating arguments from these international legal frameworks could promote accountability and end inhumane conditions in detention centers.

- In an article in the Brooklyn Law School’s Journal of Law and Policy, Sabrina Balgamwalla of Wayne State University Law School argues that ICE’s unchecked power to transfer detainees causes harms that existing procedures cannot remedy. Balgamwalla explains that these transfers—from public to private facilities, across state lines, and beyond individual courts’ jurisdiction—often place detainees in remote areas, intensifying the obstacles of defending against removal. Balgamwalla attributes this disproportionate authority to systemic failures across all branches of government: statutory and regulatory gaps that fail to constrain ICE, and jurisdiction-stripping laws that block judicial review. Balgamwalla concludes that rather than reforming transfer policies, the entire immigration enforcement model must be redone to embed meaningful safeguards for noncitizens.

- Current immigration detention jurisprudence fails to protect the substantive rights of detained immigrants, argues Alina Das of New York University School of Law in a Harvard Law Review article. Das explains that some courts have rejected legal challenges made by detained immigrants out of a reluctance to contradict the political branches. Das asserts that by assuming that the sole interest of the political branches in detention is to seclude and deport immigrants, U.S. courts fail to consider the interests of immigrants. Das contends that the political branches indeed have an interest in ensuring civil conditions for detained immigrants. Das maintains that the failure of the U.S. government to effectuate its “civil detention interest” underscores the lawlessness of the current system.

- In an article in the Virginia Law Review, Ingrid Ealy of the UCLA School of Law and Steven Shafer of the Esperanza Immigrant Rights Project argue that the unregulated design of detained immigration courts erodes due process and fundamental fairness by creating a segregated court system that systematically disadvantages detainees. The authors emphasize that detained immigration courts prioritize speedy proceedings with minimal representation by counsel, heavy reliance on video adjudication, and limited public access. Ealy and Shafer contend that the rules of these courts give the government immense power over where immigration cases are held. The authors maintain that an understanding of the structure and function of the detained immigration court system is crucial to efforts to research and reform immigration detention policy.

- In an article in the Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law, Sarah Sherman-Stokes of Boston University School of Law contends that the U.S. government’s “Alternatives to Detention” program entrenches rather than alleviates the harms of immigration enforcement. Sherman-Stokes warns against treating digital surveillance as a humane reform, explaining that such “digital cages” extend a punitive immigration system’s reach into communities. Sherman-Stokes emphasizes that electronic monitoring inflicts a hidden but serious harm and normalizes an expanded enforcement infrastructure. Sherman-Stokes calls for abolishing not only immigration detention but also its digital substitutes, insisting that true reform requires dismantling this carceral surveillance regime.

The Saturday Seminar is a weekly feature that aims to put into written form the kind of content that would be conveyed in a live seminar involving regulatory experts. Each week, The Regulatory Review publishes a brief overview of a selected regulatory topic and then distills recent research and scholarly writing on that topic.