Law students, lawyers, and academics need to reflect on efforts to make legal academia more inclusive.

In the weeks following the death of Minneapolis resident George Floyd, a death that broke an iceberg’s hull through its frigid surface, I was invited to contribute an essay to the University of Pennsylvania Law School’s The Regulatory Review.

The Review’s editors were soliciting contributions to this series of essays addressing racial inequality within regulatory law and policy. As an identity scholar, with a focus on intercultural awareness and identity performance, I was asked to comment on how structural inequality and implicit biases affect who gets to be a lawyer and who finds success at law school and beyond.

The connection to administrative law, at first, seemed tenuous, but after talking with the editor who invited me to contribute, I understood the thread to be grassroots in nature. That is, the subtle yet pernicious ways in which inequality functions to limit, or in some cases to prevent, access to success in the legal profession for traditionally marginalized voices has an endurable, albeit not immediately visible, effect on the modern administrative state.

Personally, my law school days were filled with visions of creating a career that modeled the popular television series, “Law and Order”—didn’t we all aspire to be attorney Jack McCoy, or actually, Captain Olivia Benson? And although nearly two decades have passed since my law school days, I am quite certain that I did not spend a single one considering regulatory issues or developments. And why not? I honestly do not know.

The truth is that in law school, I should have been thinking about or required to engage with regulatory law because it touches every area of my life. Regulations govern our educational experiences, the limits and reach of health care, infrastructure, our use of technology—think data privacy, artificial intelligence, and so forth—and the rights of every citizen, including immigration programs and employee protections.

But beyond my law school course selection, the question that was far more bothersome to me was: Why would I consider submitting a piece to a publication housed at an Ivy League institution? Or more frankly phrased, what are the chances that an Ivy League institution would actually consider my work—my voice?

This question loomed over me like a heavy weight, one I have grown tired of lifting. Although a lawyer and law professor, I am also an African American woman with no Ivy League pedigree in my lineage—neither personally, academically, nor professionally. And despite the accolades I have achieved along the way, it is well known that many academic journals from top or Ivy League institutions often produce and reproduce a monolithic voice.

This is not to say that scholars of color have not offered submissions. Rather, the turnstile feels to be wedged at declining to make an offer to hear our voice, with publication offers being a glorious exception instead of a frequent occurrence. To say that I am exhausted, likely along with many other scholars of color, is an understatement.

I feel both inadequate yet perfectly postured to offer sentiments on the dangers and deprivation that structural ethnic inequality and implicit biases have, not only on success in and beyond law school, but also in the daily goings-on of the American public.

On the one hand, my own aloof relationship with regulatory and administrative law during law school perhaps bears witness to the lack of influence that it was thought I would or could have in this space—I do not recall any law school professor advising me to take courses in regulatory or administrative law. Or perhaps, more deeply rooted, my lack of exposure to regulatory policy is symptomatic of the implicit assumption that law students enter law school with some network of lawyers who will mentor them toward influential course-takings; that is, those courses that move beyond a two-day bar exam and impact the very fibers of our society—in other words, our very own lives.

On the other hand, there had to have been students in law school who knew enough to take such courses. After all, we live and operate in a world governed by an intricate web of regulatory systems, and there are lawyers that are heavily influencing these spaces. The very existence of The Regulatory Review beckons awareness to this truth. Yet how these lawyers knew as law students the importance of regulatory law, or at least the educational foundation for this work, positions me squarely in a seat of guessing—undergraduate professors, family, friends, mentors, social circles? I am at a loss.

What is clear is that, despite decades of scholarship discussing the implications of laws that govern the daily lives of everyone, including people of color, journals and publications across the country appear recently to be aching for scholars of colors to fill their volumes. But have we actually been absent? Why now—amid death, violence, and riots—is my voice, our voices, so important? Is my voice only awakened or relevant in times of sorrow? I am desperate for an answer.

For weeks, after the invitation to contribute was kindly brought before me from a student editor whom I have come to treasure, I wrestled with my own reframing of the request—that is, what would the space have to look like for me to contribute?

Should The Review’s webpage virtue signal with more brown-skinned authors? Should the Home or About Us page offer yet another epilogue showing their support toward the Black Lives Matter movement? Should its Submission page indicate that it strongly encourages women and people of color to submit work? Should its site be riddled with quotes from any and all regulatory or administrative law opinions from the late Justice Thurgood Marshall or Justice Clarence Thomas? Again, I found myself at a loss. At last, after much soul searching, I have resolved that it is not my question to answer, at least not yet.

My purpose here is not to shy away from addressing the effect of structural inequality and implicit bias on who finds success as a lawyer, particularly given the dearth of diverse voices that should be contributing to the regulatory systems that govern our very lives. Nor as an identity scholar and consultant is it my desire to simply walk away and leave the proverbial ball in law students’ court. But my resistance, or silence, is in view of a deeper issue, and I pause to observe the panoply of this moment in the legal academy, a microcosm of our larger society—that now shades of brown-skin matter. Now, there is a need to both recognize the existence of and simultaneously stop normalizing the myth of whiteness.

I recently read an essay by Australian professor and author Ken Taylor, who researches cultural landscapes, reading within them their meanings and values. One quote has since gripped me. He writes:

One of our deepest needs is for a sense of identity and belonging. A common denominator in this is human attachment to landscape and how we find identity in landscape and place. Landscape therefore is not simply what we see, but a way of seeing: We see it with our eye but interpret it with our mind and ascribe values to landscape for intangible—spiritual—reasons. Landscape can therefore be seen as a cultural construct in which our sense of place and memories inhere.

Taylor goes on to comment that, although some have described the landscape as rich and pretty, the “memory of landscape is not always associated with pleasure. It can be associated sometimes with loss, with pain, with social fracture and sense of belonging gone, although the memory remains, albeit poignantly.”

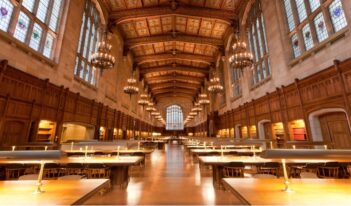

I have, since reading this quote, turned it over in my mind like the crashing waves of an ocean—each wave of remembrance a bit different and more impactful than the last. To me, the law, the legal profession is this landscape. Most certainly, for those of us within this profession, we indeed seek a sense of identity and belonging—a human attachment to this community that, though it may not define us completely, has shaped a large part of our matriculation and being. And yet the landscape of the legal profession is 86 percent white and 63 percent male. It is the cultural construct of this landscape that is troubling, if, as Taylor suggests, herein lies our “sense of place and memories.”

But my sense of place and memories are not often found in this landscape. No, too often I struggle to chisel my brown skin into the rich and pretty traditions, norms, and policies whose origins I had no say in constructing—defending my voice when it butts up against this pristine landscape.

Now, as loss and pain of recent events have shifted this landscape, revealing its cracks and fissures, my need to chisel feels halted. As I stand to dust myself off, binding up wounds, I wonder for a moment, perhaps naively, did I break through? Yet as I look around, I am brought back to reality.

The landscape right now is painful and bleak. So, if you seek my voice, I too seek yours. Why does the ugliness of the current landscape, unveiled through death and violence, now render me visible? Again, I am desperate for an answer, because without one I see no reason to acquiesce.

This essay is part of a series entitled Racism, Regulation, and the Administrative State.