The SCRUB Act would help correct regulatory accumulation – but the bill could be improved.

The existing regulatory process keeps most people’s attention focused on new rulemakings, but some recent legislative proposals have helpfully contemplated changes to that process that would increase the role for retrospective review of the existing stock of regulations. One of these bills is the Searching for and Cutting Regulations that are Unnecessarily Burdensome Act, or the SCRUB Act, on which earlier this year I testified before the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial, and Antitrust Law. This bill would make important strides toward addressing a growing problem of regulatory accumulation, but it also needs some enhancements to make retrospective review of regulations more meaningful.

My own research has led me to conclude that meaningful retrospective review will only be accomplished through an act of Congress. The potential gains to individuals, businesses, and even to government agencies make the implementation of a process for meaningful retrospective review vital to sustaining economic growth without sacrificing important achievements and objectives in areas such as workplace safety and environmental stewardship.

Recognition of the need to reduce the existing regulatory burden is neither new nor partisan. Every administration since Jimmy Carter’s has undertaken efforts to modify or eliminate obsolete, duplicative, ineffective, or inefficient regulations. There is a good reason for this: regulatory accumulation can negatively affect GDP growth. A recent study found that, between 1949 and 2005, the accumulation of federal regulations in the U.S. slowed economic growth by an average of two percent per year. Several earlier studies using broad cross-country indices, such as those produced by the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), similarly reveal the negative impacts regulation can have on economic growth.

Despite the efforts of several administrations, the U.S. regulatory system has no working, systematic process for reviewing regulations for obsolescence, duplication, or poor performance. Over time, this has facilitated the accumulation of a vast stock of regulations. From 1975 to 2012, the number of pages in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) grew from just below 75,000 pages to nearly 175,000 pages.

Another way to measure regulatory accumulation is to examine restrictiveness. By design, regulations restrict choices. In its most basic definition, a regulation is a law that “seeks to change behavior in order to produce desired outcomes,” and it does this by requiring or forbidding certain actions. Using RegData (a publicly available regulatory database I compiled with my colleague, Omar Al-Ubaydli), I tracked the number of restricting words printed in the CFR each year, such as “shall,” “must,” or “required.” The total number of restrictions in federal regulations has grown from about 835,000 in 1997 to over 1 million by 2010. Over time, these accumulated restrictions can either directly foreclose paths to innovation or entrepreneurship or add up to the point where their cumulative cost makes certain actions prohibitively expensive. Indeed, in the long run, it is likely regulation’s collective impact on innovation and entrepreneurship impedes economic growth.

My colleague Richard Williams and I have documented several presidentially led efforts at retrospective review. In our view, every attempt by presidents to direct agencies to review their own regulations has yielded poor results. Even the most successful of these efforts failed to reduce substantially the volume of regulations in the CFR, and none of these efforts had a lasting effect on the long-run growth of the CFR.

The failure of past regulatory reviews likely stems from fundamental misalignment of incentives: agencies, despite direction from the president, have incentives to maintain and grow their regulations in order to maximize their budgets and control over their portion of the economy. In turn, in order to retain regulations that would be eliminated otherwise, agencies may either hide or fail to produce information that would help identify obsolete or ineffective regulations in the first place. We should not expect agencies to give any better assessments of their own rules than professors would expect of students grading their own tests.

This is not to disparage the efforts at retrospective review by the current administration or similar efforts attempted by previous administrations; in fact, these efforts can have marginal impacts on a limited number of rules and may be worth doing in the absence of congressional action. But they have clearly failed to reduce overall regulatory accumulation. Retrospective review, and perhaps prospective regulatory analysis as well, should instead depend upon independent assessors.

Richard Williams and I examined two successful government reforms that overcame similar obstacles to those facing regulatory reform efforts: the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Commission in the United States, and the Dutch Administrative Burden Reduction Programme. The BRAC Commission, first established and used in the 1980s, overcame an impasse very similar to that of regulatory accumulation: nearly everyone agreed that, toward the end of the Cold War, many military bases were no longer necessary, but no one could agree on which specific bases to close. The Dutch Programme, launched in 2003, successfully eliminated 25 percent of the administrative costs imposed by regulations. In both cases, an independent commission or monitoring agency was given a clearly defined mandate with clear, simple, and transparent criteria.

We conclude that successful regulatory reform legislation will need similar characteristics. A complete list of helpful features to a robust retrospective review process would include most or all of the following:

- The process should entail independent assessment of whether regulations are functional or nonfunctional.

- The process should ensure there is no special treatment of any group or stakeholder.

- The process should use a standard method of assessment that is difficult to subvert.

- Whatever the procedure used, assessments of specific regulations or regulatory programs should focus on how well the regulations or programs led to the outcomes desired.

- Regulatory agencies should be recognized as important stakeholders, with incentives to keep and increase regulation.

- Congressional action – such as a joint resolution of disapproval – should be required in order to stop recommendations about regulations and regulatory programs.

- The review process should repeat indefinitely.

The SCRUB Act contains some, but not all, of these features. The Act would create a commission consisting of independent appointees. This commission would have the authority to hire analysts and experts necessary for an assessment of rules and to collect essential information for those purposes. The SCRUB Act would also require the commission to follow a predetermined methodology that considers, among other criteria, rules’ effectiveness, efficiency, ongoing costs relative to benefits, duplication, and obsolescence to determine which rules should be eliminated or modified.

Under the SCRUB Act, rules selected for modification or elimination would be placed in one of two categories. The first category of rules would be “fast-tracked” for modification or elimination by some (presumably) short-term target date set by the commission.

The second category of rules would create the basis of a one-in, one-out procedure called “CUT-GO.” When an agency creates a new rule, it would be required to eliminate a rule or rules designated for CUT-GO until the net effect is zero cost. In other words, the agency would offset the costs of each new rule by eliminating or modifying old rules placed in this second category.

The SCRUB Act could be improved if it were modified to limit formally Congress’s ability to subvert the process of selecting rules for elimination or modification. As the creators of the BRAC process recognized, every base targeted for closure had a champion defending it in Congress – the members whose constituencies would be affected by the closure. So it would likely be with regulations slated for revocation. A better solution would be to follow the BRAC experience and require that a SCRUB Act commission’s recommendations would take effect automatically unless Congress were to enact a joint resolution of disapproval of the entire set of recommendations – with no amendments allowed.

The existing regulatory process in the U.S. is one-sided, with analysis only playing an institutionalized role before rules are adopted. The lack of any systematic process for retrospective review leads to regulatory accumulation that has economic consequences. To make progress reducing the ill effects of accumulation, it makes sense to establish a more robust, institutional process for modifying or eliminating regulations that are no longer useful.

This essay is part of The Regulatory Review’s five-part series, Debating the Independent Retrospective Review of Regulations.

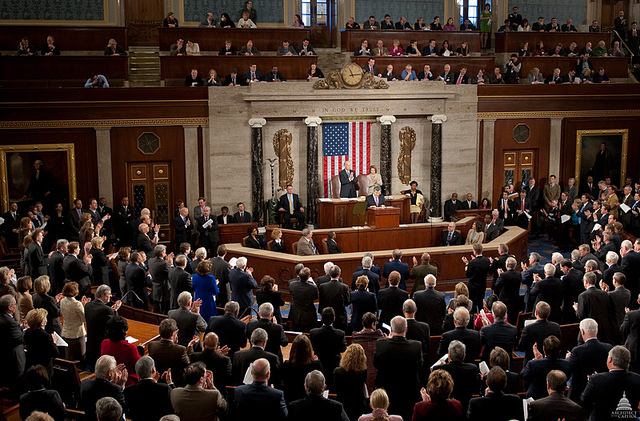

Pictured in the text is the House Chamber, also called the Hall of the House of Representatives. Photo Credit: Architect of the Capitol.