Scholar calls on FDA to prioritize public health by reforming medical device regulation.

Bella is a high-achieving thirteen-year-old. She takes college-level courses, is a four-sport athlete, and mentors special needs children. None of this, however, would be possible if she had never received the Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) therapy that addressed her epilepsy symptoms when she was eight months old.

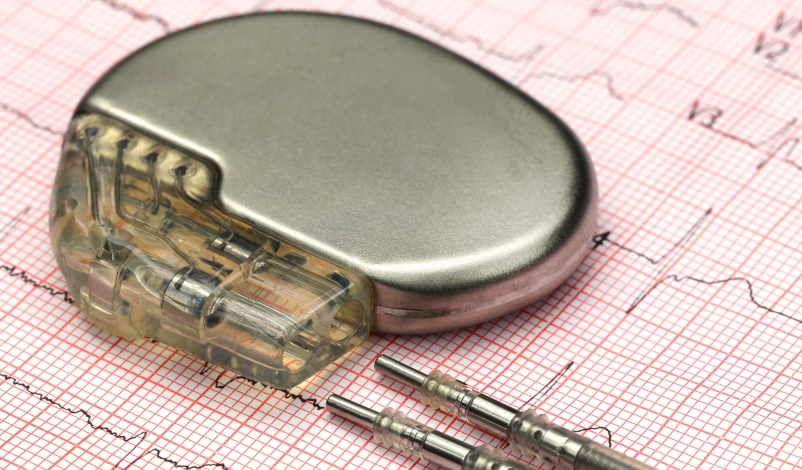

Although the VNS therapy has allowed Bella to have a promising childhood, it is delivered by implanting a medical device in patients, a device that receives less stringent regulatory oversight in the United States than most other medications. Tragically, medical devices have contributed to the deaths of hundreds of Americans each year.

According to data from the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA), more than 80,000 deaths and 1.7 million injuries have been linked to medical devices in the past decade. In a forthcoming article, law student William Chanes Martinez argues that the medical device safety crisis relates to FDA’s failure to regulate those products and their manufacturers adequately. The current crisis, Martinez contends, will only worsen unless proposed reforms place pressure on FDA.

The United States currently makes up 40 percent of worldwide revenue and sales from medical devices—the largest medical device market in the world. Roughly 10 percent—or approximately 32 million Americans—have an implanted medical device.

Because there were limited guidelines for monitoring the medical device industry at the beginning of the 20th century, medical devices were not adequately regulated by the federal government.

Then, the U.S. Congress passed the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 (FDCA) in an attempt to address the gaps and better protect consumers. Despite the passage of this legislation granting FDA the authority to regulate the industry, medical devices remained largely unregulated because their oversight was limited to “ensuring that devices were not adulterated or misbranded,” according to a study of FDA’s review processes.

Martinez suggests that, in the absence of adequate regulation, FDA should take several actions: reinstate requirements for manufacturers to publish all medical device approvals and their supporting rationales; extend mandatory medical device-related reporting to all medical professionals who use medical devices in their practice; and eliminate its Voluntary Malfunction Summary Reporting program, which gives manufacturers discretion to report certain device malfunctions instead of requiring disclosure.

The medical device problem, according to Martinez, is caused by manufacturers that are motivated to market new devices quickly—despite the industry’s awareness of unsafe or ineffective medical devices. Martinez argues that because FDA prioritizes “innovation over safety,” it encourages device manufacturers to take shortcuts that endanger public health.

In the medical device industry, FDA organizes devices into three classes—Class I, II, and III. Martinez explains that Class I devices present the fewest number of risks to human safety, Class II devices are medical devices where the general controls are “insufficient to ensure their safety and effectiveness,” and Class III devices present the highest number of risks to the public—and should be required to have the strictest regulatory controls.

FDA’s current pre-market approval processes allow the majority of Class II devices—which receive far less scrutiny than Class III devices—to enter the market as long as they are “substantially equivalent to a predicate device” that the agency has already cleared or approved for sale, Martinez explains. Accordingly, Martinez observes that “FDA rarely inspects device manufacturing facilities or requires device manufacturers to conduct clinical trials before it clears a device for market distribution.”

Although FDA has the authority to reclassify medical devices and subject them to more stringent pre-market approval requirements after they are released to the market, FDA often only does so after patients are injured by defective devices. Often, as Martinez points out, even if stricter requirements are eventually enforced, consumers who are using older devices remain unaware of the new requirements.

For example, after a faulty metal-on-metal hip implant device left a patient with permanently destroyed muscles, tendons, ligaments, and vital organs, reclassification of the device forced manufacturers to stop marketing the product and undergo a series of new requirements before resuming sales. Martinez claims, however, that FDA continued to mislead the public about the implants’ health risks even after the hip implant device underwent reclassification.

According to Martinez, FDA has experienced many other instances of potential negligence, such as when the agency ignored risks detected during the pre-market clinical trials for various medical devices.

For example, an FDA advisor flagged high death rates associated with VNS therapy after clinical trials ended. Despite the warning, the device was still approved for market distribution without requiring that the manufacturer inform patients about the device’s mortality risks. Although FDA made its approval contingent upon the manufacturer conducting “post-market safety studies on the device,” the device entered the market despite its inefficiencies, Martinez states.

The hope for a system that strategically regulates medical device manufacturers is centered around FDA involvement, Martinez recognizes. Although it has made changes to its regulatory processes since the passage of the FDCA, the agency must develop new procedures that force manufacturers to be methodical and to promote safety.

Ultimately, medical devices have the potential to improve the lives of millions of Americans. But Martinez argues that, without the proper regulatory framework provided by FDA, the medical device industry will continue to compromise public health.