The booming U.S. egg donation industry requires more regulation to safeguard donor welfare.

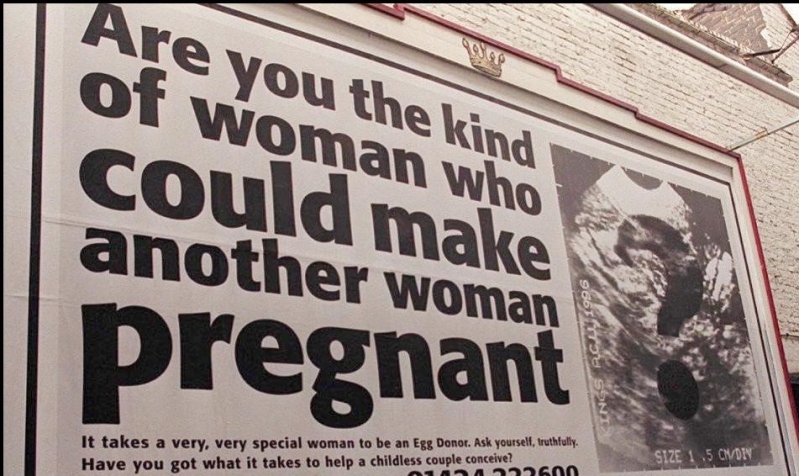

“Earn up to $50,000 dollars!” “Help a family!” “Donate your eggs!”

Such slogans appear regularly on college bulletin boards and the social media feeds of many young women across the United States, advertising the altruistic—and financial—benefits of donating their eggs to would-be parents.

But behind these advertisements lies a poorly regulated industry that buys and sells human eggs, with potential negative health effects for donors.

Unlike countries such as the United Kingdom and Canada, the United States has no federal regulations that specifically address advertising to potential egg donors. No U.S. agency tracks the long-term health effects of egg donation. And there is little oversight of the donation process—which involves injecting someone with hormones for at least ten days, and then piercing the vaginal wall with a thick needle to extract eggs from the ovary.

Initially, it may seem that egg donation businesses are at least somewhat regulated. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), after all, oversees any establishment that recovers, processes, or distributes human reproductive tissue, including eggs. These clinics must register with FDA and list their “tissue-based products” in accordance with federal standards, which also require that egg donors be tested for infectious diseases.

But although FDA has published guidance documents on egg donor eligibility, it has taken few steps to ensure that donors are treated fairly by egg donation businesses. In short, FDA regulates who can be an egg donor—but does not regulate how the for-profit egg donation industry treats donors.

And although payments for organ donation have been outlawed in the United States since 1948, paying egg donors is entirely legal. Economic inducements are potentially limitless, despite egg donation businesses’ insistence that the industry is driven by altruism and “women helping women.”

Certainly, the thousands of donors who pay off student loans and other expenses through egg donation payments understand the industry’s economic value. Compensation for a single donation can range from about $5,000 to $50,000—depending on factors such as a donor’s physical profile, SAT scores, and athleticism.

The advertisements that recruit these donors are also underregulated. Although federal agencies enforce general “truth in advertising” laws, rarely if ever have these general requirements been applied to advertising for egg donors. Only one state has moved to clarify what truth in advertising means in the egg donation context. Passed in 2009, a California law requires that egg donor advertisements with compensation information must also feature warnings about health risks.

Unfortunately, such health risks may be haphazardly disclosed and are not well-studied. A survey of egg donors concluded that most donors were not informed fully of health risks prior to their donation. Short-term side effects from donation—such as bleeding and infections—are often not reported, as clinics rarely follow up with donors. Although some donors later report health problems such as ovarian cysts and infertility issues, the potential long-term risks of egg donation are not well-known. Some studies have also linked an increased risk of cancer with hormone stimulation of egg production.

These uncertainties persist as the egg donation market continues to grow. The number of women donating their eggs soared from 10,801 in 2000 to 18,306 in 2010—a 70 percent rise, motivated in part by the “growing practice” of delaying pregnancies and an increasing demand for assisted reproductive technology. By 2018, industry analysts valued the U.S. market for egg donations at $487 million. Prominent egg donation businesses—bearing names such as Extraordinary Conceptions and Premier Egg Donors—have engaged in a series of investor-driven mergers and acquisitions in recent years.

Yet government regulation has failed to keep pace with this industry growth. Two professional organizations have tried to create “self-regulatory” guidelines for egg donation businesses—but only with mixed success.

The Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology’s minimum training standards for clinic employees have been largely uncontroversial. But another organization, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), faced litigation after it attempted to restrict egg donor compensation. ASRM advised that payments above $5,000 “require justification” and that sums above $10,000 are “not appropriate.” In response, four egg donors sued the organization, arguing that the price caps undercompensate women for a “painful and risky” procedure. After four years of litigation, in 2016 the organization agreed to strip the financial caps from its guidelines.

ASRM also insists that egg donors are “owed the same duties present in the ordinary physician-patient relationship.” But the egg donation model complicates this duty of care, as doctors employed by egg donation businesses are financially motivated to ensure that women donate their eggs. One researcher posing as a potential egg donor observed that physicians were “focused primarily on the infertile recipients” of the eggs—and less on the donor undergoing invasive surgery.

These ethical issues in the egg donation industry may be addressed by a variety of regulatory solutions. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services could establish a National Egg Donor registry and initiate more government-funded studies on the long-term effects of donation. Such efforts may provide potential donors with “unbiased” information, rather than forcing them to rely on egg donation businesses for advice. In addition, the Department could use rulemaking to elevate private health organizations’ physician-patient care and compensation cap guidelines into federal law.

On a more structural level, the “fragmentation” of the U.S. healthcare system may impede better tracking of the health effects of egg donation. The uninsured, financially driven donation process used by U.S. egg donation businesses disconnects donors from their general healthcare provider. In contrast, by prioritizing the health of donors and providing insurance coverage for egg donation, Scandinavian countries with nationalized health care systems have produced “robust” data on the health effects of reproductive technology procedures.

Although the future of egg donation regulation may be uncertain, for now it is clear that the allure of up to five-figure payments provides “fertile ground” for ongoing ethical and medical concerns that merit better regulation to protect donors.