Study indicates a vital judicial role in overseeing defendants’ reentry following prison.

In most cases, individuals’ release from federal prison does not mark the end of their sentences. A federal criminal sentence typically also includes a term of “supervised release,” which the U.S. Sentencing Commission defines as a “unique type of post-confinement monitoring that is overseen by federal district courts with the assistance of federal probation officers.” Supervised release is intended to assist people who have served prison terms with their effective reintegration, or “reentry,” into the community.

Judges are not always actively involved in overseeing supervision. Rather, officers of the U.S. Probation Office play the dominant role in monitoring individuals on supervised release. Judges tend to become more involved only after a supervisee has failed to comply with the terms of supervision. As a result, judges may miss the opportunity meaningfully to assist with reentry and to help ensure that necessary services such as drug treatment, mental health counseling, and housing and employment assistance are provided.

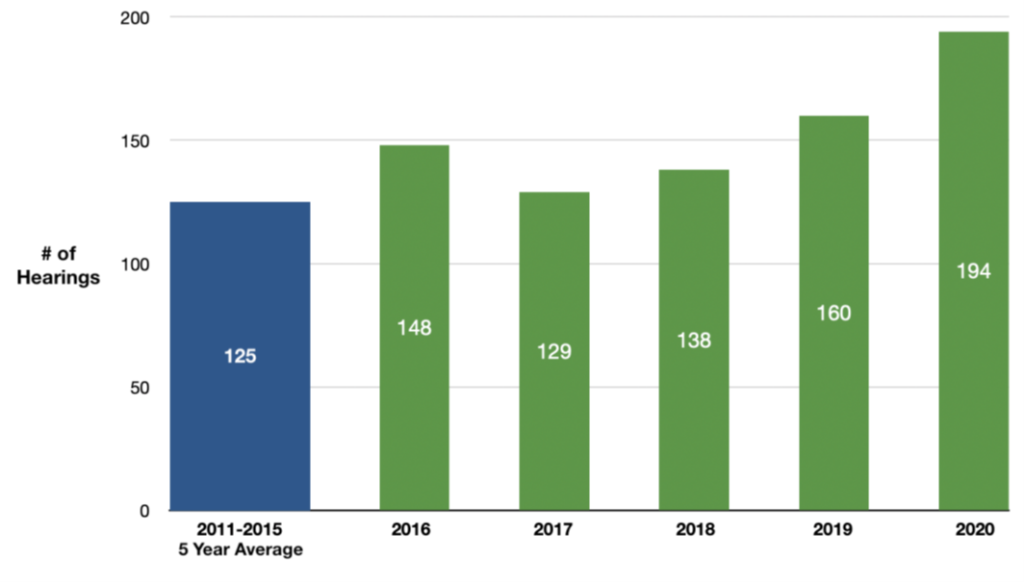

Over the past five-plus years, my chambers staff and I developed a more active and involved approach to supervised release. The practice features regular supervised release hearings intended to help ensure that supervisees succeed and avoid further negative involvement in the criminal justice system. Importantly, this practice also includes early termination of supervised release for all those who have shown that they no longer need supervision.

We worked with 152 supervisees during the period January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2020, and we recently prepared a report describing reentry outcomes for the 152 supervisees in our “study population.” There was no control group in our study.

We have concluded that increased judicial involvement in supervised release meaningfully can help supervisees with successful reentry, as measured by such factors as fewer felony arrests and serious probation violations. Four findings of our modest study are offered here for discussion and as directional guidance for those who may be interested.

First, judges can absolutely smooth the path to reentry by conducting supervised release hearings with the relevant stakeholders, starting soon after supervisees’ release from prison. The goals of these hearings are active listening, encouragement, and assistance with mental health counseling and drug treatment programs, housing, and gainful employment. The number of hearings is determined by the court with input from the parties and is a function of how well the supervisee is able to meet the “conditions” (or requirements) of supervision and otherwise adjust to reentry.

At the hearings, the supervisee’s probation officer usually leads off with an update of key issues in supervision (and often submits a brief written status report prior to the hearing). The supervisee is the next to speak and brings everyone up to date. The therapist’s and the drug counselor’s viewpoints are included because we have found their input to be invaluable. By their choice, defense and government counsel generally have less to say than they do during most other criminal proceedings, but they are nevertheless instrumental. The court proactively joins in throughout each hearing, providing support and (hopefully constructive) criticism, and proposing goals and options. The hearings are open to the public and they include testimony, exhibits, and a written verbatim transcript.

The chart below illustrates the number of hearings held during each year of the five-year study period (2016–2020) examined in our report.

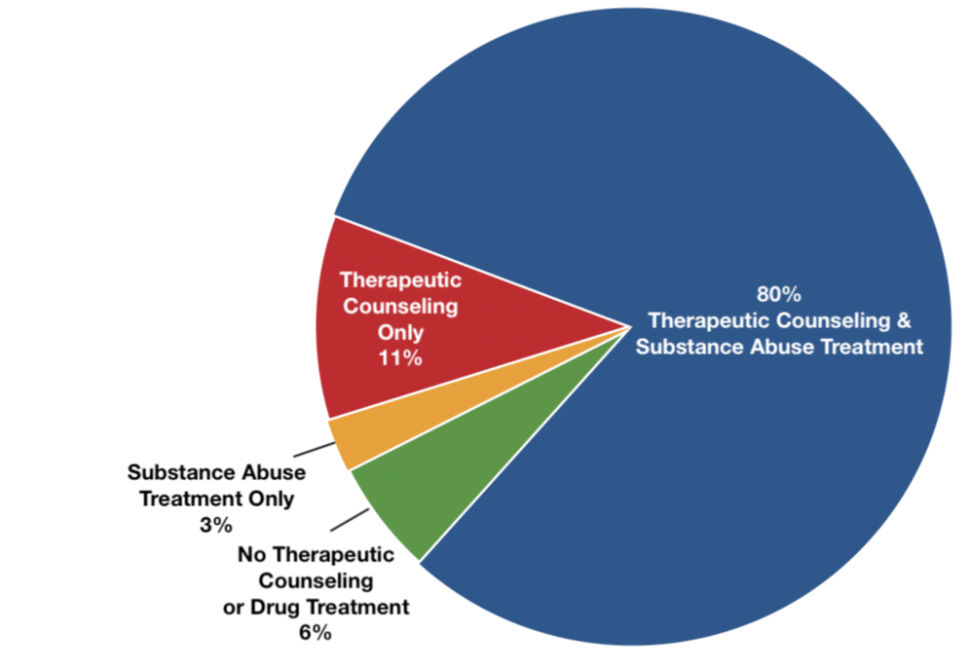

Second, the key resources during supervision are often regular mental health counseling and substance abuse treatment. In this regard, it may be helpful for the court at sentencing to specify and require participation in mental health counseling and drug treatment as “special conditions” of supervision, assuming those conditions are warranted under section 3583(d) of the federal sentencing statute. For example, the judgment of conviction (which sets forth the details of the defendant’s sentence) might include the following: “Throughout the term of supervised release, defendant shall participate in weekly therapeutic individual and group counseling by a licensed therapist. . . . Defendant shall also participate in a program approved by the U.S. Probation Office for substance abuse.” The court has the authority to require special conditions under section 3583.

The chart below shows that, from 2016 to 2020, 123 supervisees—or fully 80 percent of our study population—participated in therapeutic counseling and substance abuse treatment. Sixteen supervisees (11 percent) participated in therapeutic counseling only, and five supervisees (3 percent) participated in substance abuse treatment only.

At two recent supervised release hearings, the importance of therapy was apparent:

- Supervisee: “I think if I had been left to my own devices, I would be dead right now. I’m one of those addicts who doesn’t know how to stop. . . . I came in here broken, feeling hopeless, very much alone, isolated . . . addiction will do that. And being put into treatment and being held accountable through random drug tests and through reporting to your Honor and attending 12-step meetings, all of the things that I did, my therapist, my psychiatrist, gave me a community of support that I was completely lacking, and here I stand today. I could not have envisioned that I would be here in this position today, a totally changed man. I’ll just conclude that I’m extremely grateful.”

- Supervisee’s Therapist: “I’ve been extremely impressed with the supervisee. It has been an incredible journey. We see each other weekly. . . . A tremendous amount of development and growing up had to take place . . . I’ve been pretty impressed with the hard work and dedication that he has put forth in taking all of these things into account, and working hard in therapy, and digging in to getting skills to manage . . . his prolonged substance abuse history. And really we’ve worked hard to get him skills-based and dynamic-based therapy to learn to navigate the hurdles that have come at him. And frankly, I mean, it’s been surprising and impressive how well he’s done it.”

Third, the importance of early termination of supervised release cannot be overstated. Section 3583 authorizes the court to terminate supervision early, provided that the supervisee has completed one year of supervision and the court is “satisfied that such action is warranted by the conduct of the defendant released and the interest of justice.” Early termination is a critical incentive and a meaningful reward. It is often a welcome counterpoint to the length and severity of prior incarceration.

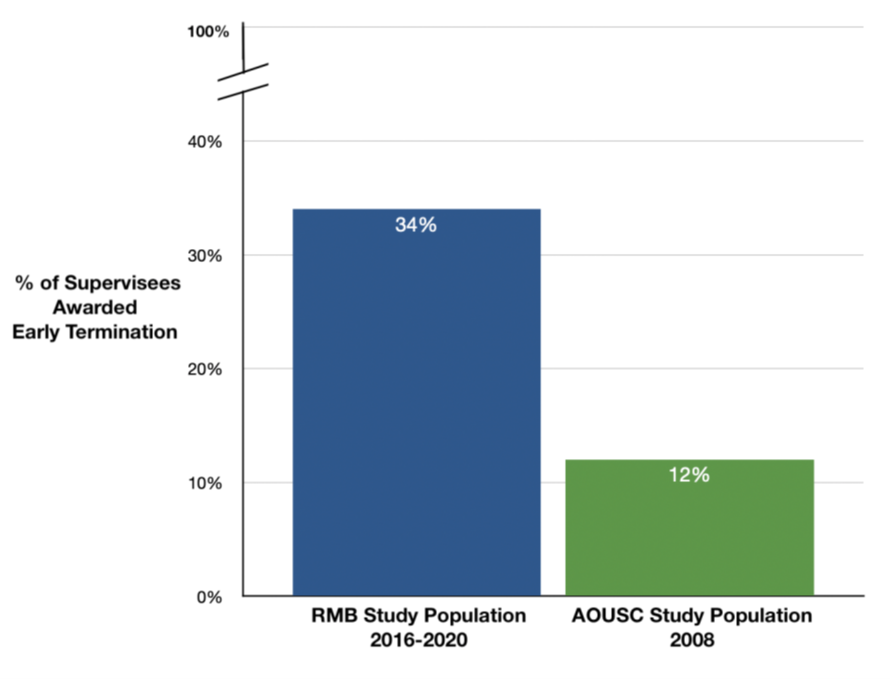

As the following chart illustrates, we granted early termination to 34 percent of our 152 supervisees. A 2010 nationwide study of data compiled by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts reported early termination of 12 percent of its study population of 35,724 supervisees.

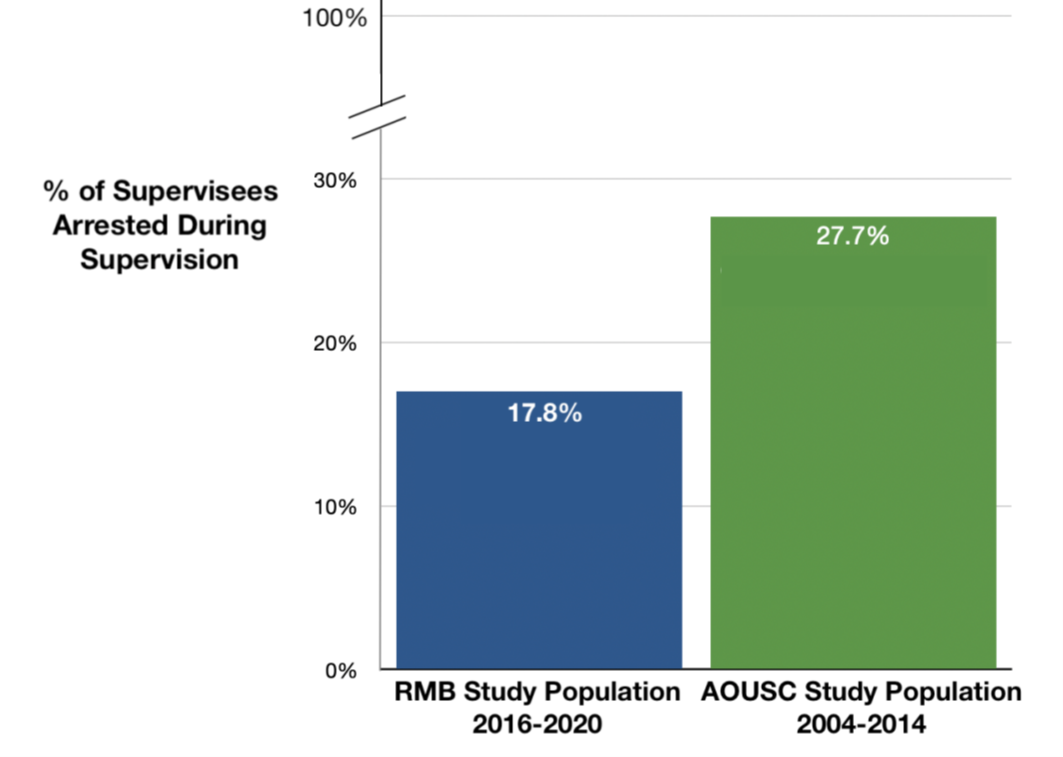

Fourth, court-involved supervision may help in reducing recidivism. As the chart below illustrates, 17.8 percent of our 152 supervisees were arrested for a felony while on supervision. A 2015 nationwide study by the Administrative Office found that 27.7 percent of 454,223 supervisees had been arrested for a “major offense” (the equivalent of a felony) during supervision.

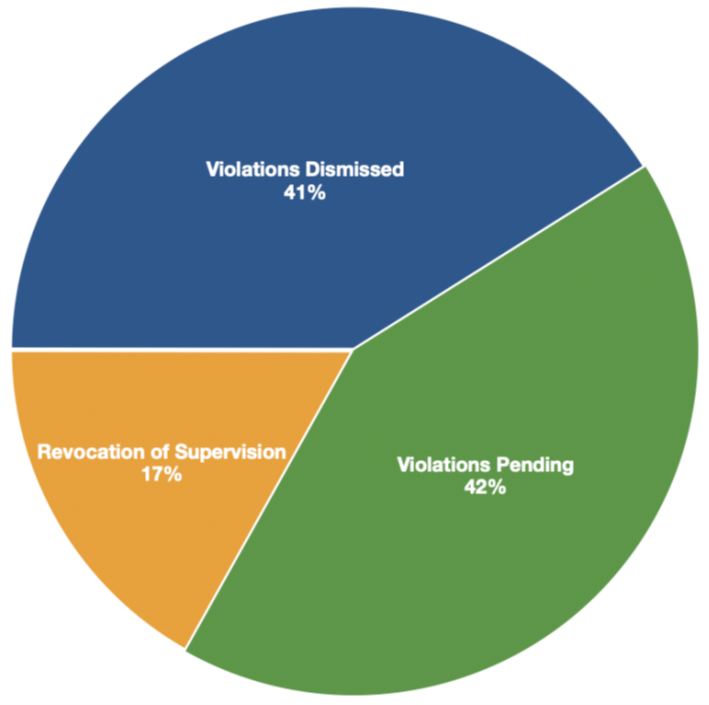

The data on probation violations are similarly encouraging. A probation officer may file a probation violation against supervisees who are arrested for a crime or fail to abide by other conditions of their supervision, such as regular attendance at mental health counseling and drug treatment. As reflected in the chart below, 124 of 302 violations filed against our supervisees (or 41 percent) were dismissed by the court and 127 violations (or 42 percent) are pending. Relatively few of the 302 violations—51 (or 17 percent)—resulted in the court’s revocation of the supervisee’s term of supervision.

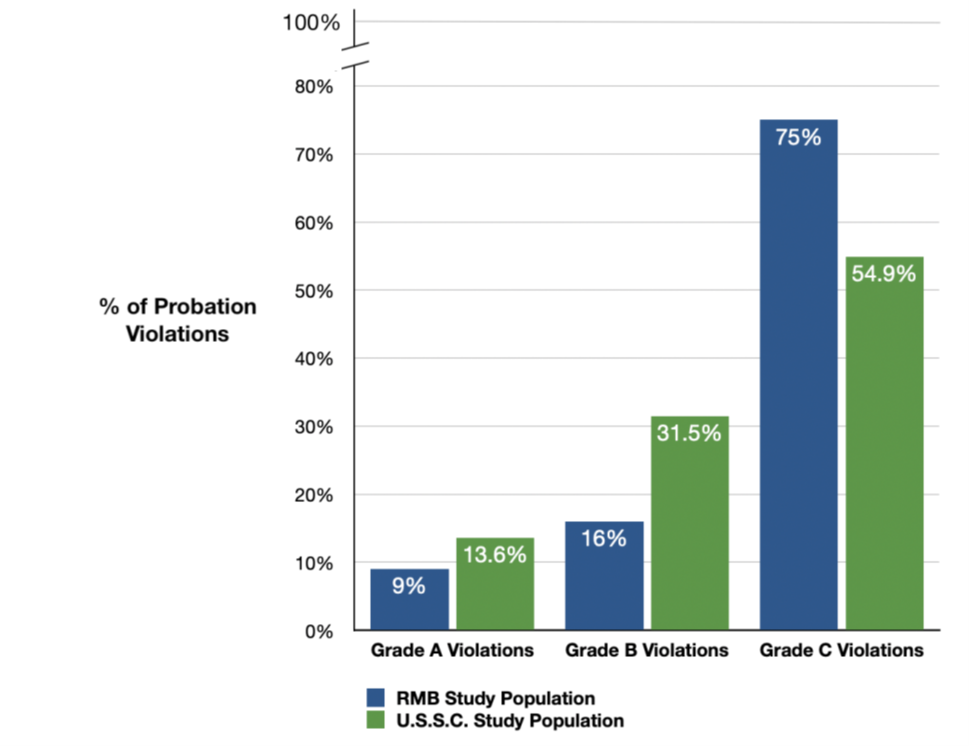

And, relatively few serious probation violations were filed against our study population of supervisees. That is, 9 percent of violations were Grade A violations (considered the most serious category, which includes “crimes of violence,” “controlled substance offenses,” and “offenses punishable by a term of imprisonment exceeding twenty years”). Sixteen percent were Grade B violations (the next most serious category, which includes offenses “punishable by a term of imprisonment exceeding one year”). The overwhelming majority of violations—75 percent—were Grade C violations (considered the least serious category, which often have involved the supervisee’s failure to attend substance abuse and mental health treatment).

In a 2020 nationwide study of 82,384 supervisees conducted by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, 13.6 percent of the violations were Grade A violations; 31.5 percent were Grade B violations; and 54.9 percent were Grade C violations.

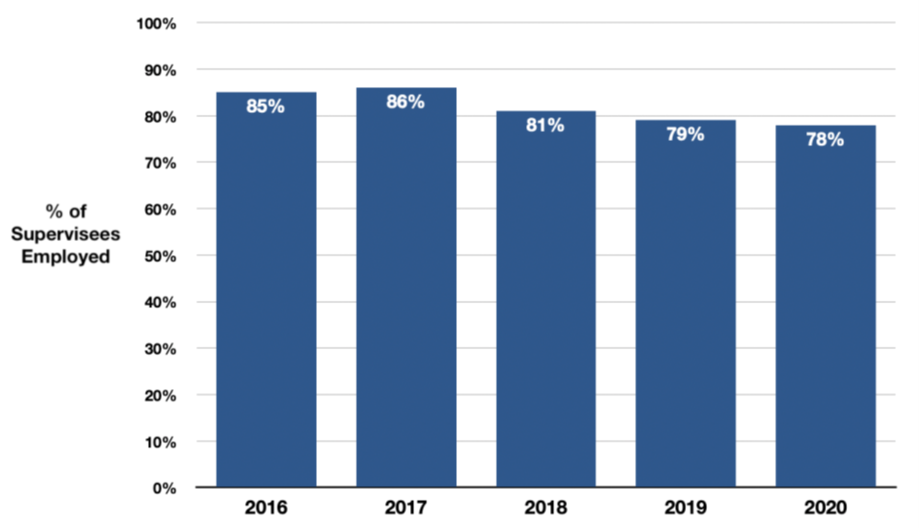

Most supervisees in our study population also obtained employment. It should be noted that “employment” is defined expansively as: “any work at all for pay or profit . . . . This includes all part-time and temporary work, as well as regular full-time, year-round employment.” The chart below reflects the percentage of supervisees who either were employed or had obtained employment in a calendar year.

I fully recognize the differences, including study population size, among and between our study population, the two Administrative Office study populations, as well as the U.S. Sentencing Commission study population mentioned above. I nevertheless agree with Professor Nora Demleitner of Washington and Lee University School of Law, who reviewed our study and concluded that our data are “quite encouraging on the recidivism and re-incarceration front.”

Active judicial participation in supervised release is challenging. It is also extremely rewarding, and it is vitally important. Professor Tina Maschi of Fordham University’s Graduate School of Social Service, whose work focuses on reentry and who also reviewed our study, very much supports judicial involvement in supervised release—as I do. Professor Maschi said judicial involvement in supervised release “incorporates a much-needed holistic portrait of the perspectives of the supervisee, the parole or probation officer, and other associated professionals . . . to foster successful reintegration into society. It also has the serendipitous effect of reducing crime and recidivism.”

This essay draws on Judge Berman’s Supervised Release Report issued on April 6, 2021.