Recent research casts doubt on the existence of a conspiracy by civil servants against the President.

President Donald Trump’s supporters have blamed many of his early difficulties on recalcitrant permanent bureaucrats and Obama Administration holdovers. In a more sinister vein, the President’s supporters have decried a “deep state” of deeply embedded bureaucrats working actively to thwart the new President’s agenda.

Is there such a thing as a deep state? If so, what is its relation to professional government? These are important questions since one of the central questions of democratic governance, as highlighted in Paul Verkuil’s Valuing Bureaucracy: The Case for Professional Government, is how to build and maintain a competent administrative state. Central to Verkuil’s argument is a belief in the importance of a neutral expert public administration that can serve either party in an equally professional way.

The answer to the question of whether there is a deep state depends upon what version of the deep state claim a person wants to evaluate. One form of the deep state claim focuses on liberal bias in the post-New Deal bureaucracy. Another version is spookier, and less partisan, focusing on powerful, but unidentified bureaucrats that really run things with no meaningful accountability. The former narrative is plausible. The latter is the stuff of movies that the paranoid or opportunistic enjoy peddling to titillate or mobilize supporters.

Charges of bias or active resistance in the civil service coming from the White House are incredibly important for professional government. The administrative state derives an important part of its legitimacy in our democratic system from its non-partisan professionalism. If elected officials undercut popular belief in the political neutrality of the civil service, the consequences can be dramatic. If elected officials persuade the public that the civil service is biased, recruiting and retaining professionals in government becomes more difficult.

Charges of political bias also can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. If elected officials do not express faith in the ideal of neutrality and articulate confidence in the ability of these professionals to demonstrate neutral competence, the norms that shape individual identity and workforce culture begin to break down. As judges must believe that the law and case facts determine outcomes, so civil servants must believe that neutral competence is what they should expect and what they should aspire to.

But is there in fact a liberal resistance to the Trump Administration? There are two claims here. The first is that liberals dominate government, and the second is that they will not obey the commands of the President. In a recent survey of federal executives I conducted with Mark Richardson, a Ph.D. candidate at Vanderbilt University, 44 percent of respondents identified as liberal, 35 percent as moderate, and 21 percent as conservative. Still, this does not tell the whole story.

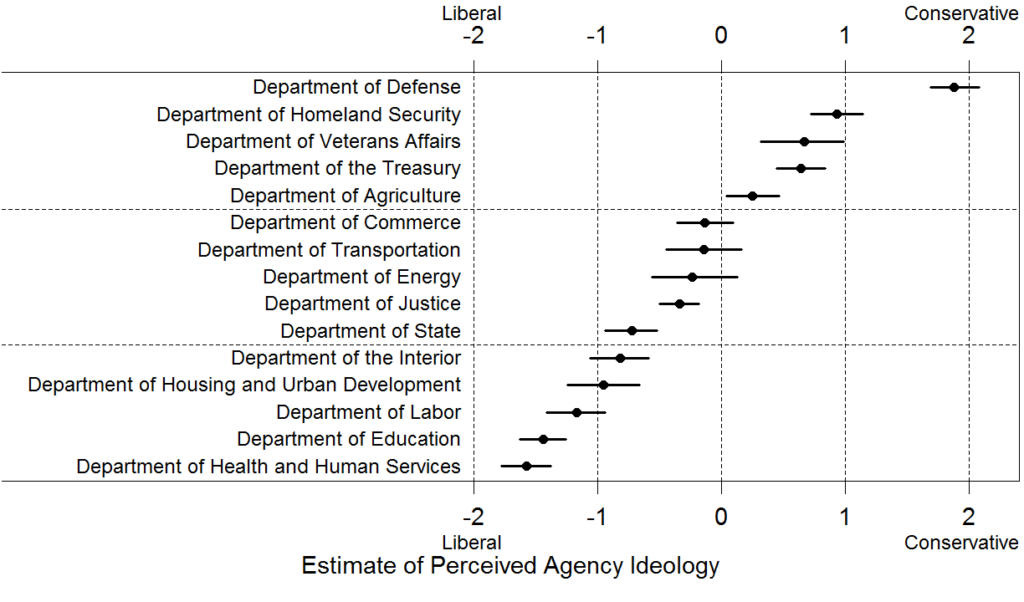

In research with Richardson and Josh Clinton, a professor at Vanderbilt, we set out to map more fully the ideological contours of the federal executive establishment. Specifically, we asked our survey respondents to list the three agencies they worked with the most. We then proceeded to ask executives whether these other agencies, plus a few others we asked them about, tended to “slant liberal, slant conservative, or neither consistently in both Democratic and Republican administrations.” We aggregated their responses to map the perceived ideological leanings of different agencies. Figure 1 graphs the estimates for the executive departments, with higher numbers reflecting perceptions of a greater degree of conservatism.

Figure 1: Perceived Ideology of Executive Departments

One interesting feature of the figure is how federal executives perceive some of the departments as liberal and others as conservative across Democratic and Republican administrations. So, if there is a liberal resistance it must be operating more in some departments than others.

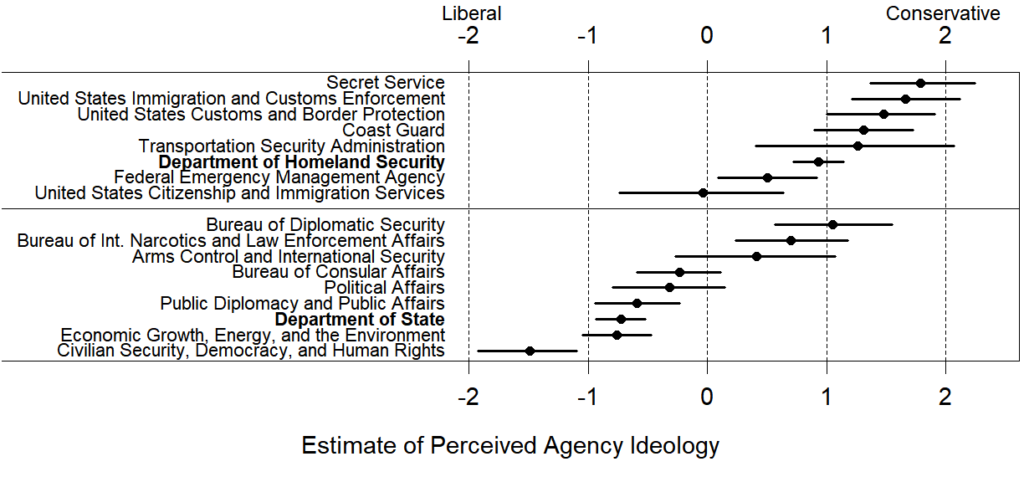

In fact, a deeper dive reveals significant variation even within individual departments. Figure 2 includes estimates of the major bureaus within two departments, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the U.S. Department of State. Among the most conservative bureaus are those involved in immigration, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The unions for workers at these agencies endorsed President Trump during the 2016 presidential campaign. There have been few complaints about a deep state operating in these agencies.

Figure 2: Perceived Ideology of Bureaus in the Departments of Homeland Security and State

This analysis also highlights the stickiness of ideological leanings across administrations. The ideological character of departments appears to persist whether a Democrat or a Republican is in the White House.

Why might that be? President Trump’s statements suggest that the bureaucracy’s ideological leanings are due to the views of the people that work in the agency. Yet, how could a merit-based hiring process lead to such an outcome? The answer lies in the fact that the policies that some agencies carry out are more liberal or conservative than others. For example, some agencies regulate banks, while others protect national security. Any civil servant carrying out the law will be carrying out a naturally liberal or conservative policy, regardless of the civil servant’s own views. In addition, at the margins liberals and conservatives may also self-select into different types of agencies. Liberals, for example, may be more likely to want to work for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and conservatives for the Central Intelligence Agency.

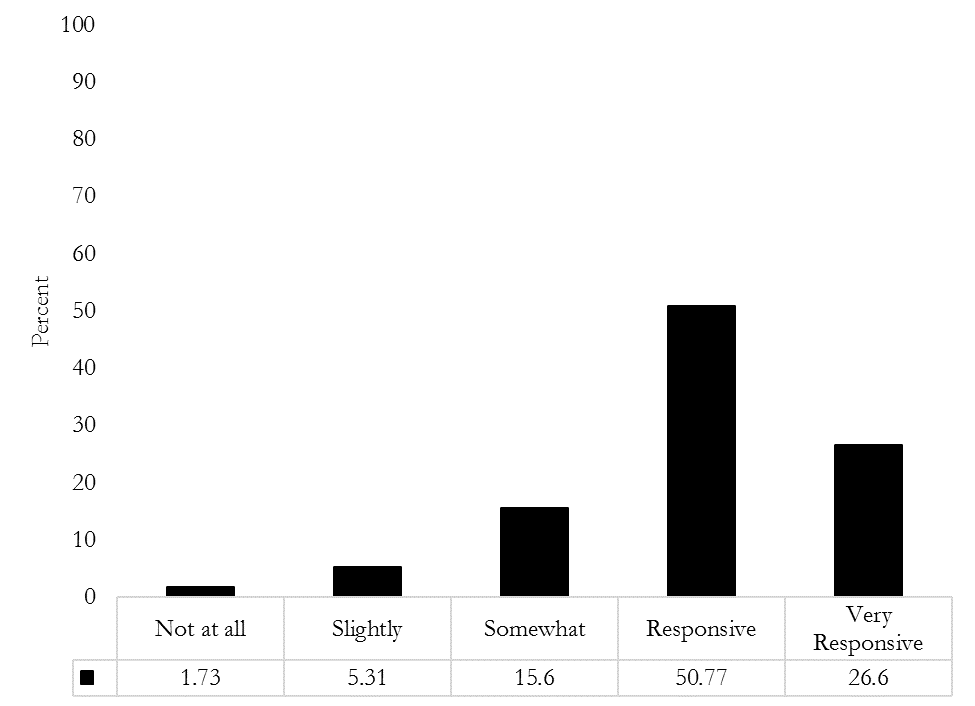

This raises the natural question of whether civil servants will work with a President with whom they disagree. There are no easily available data yet from the Trump Administration, but we do have some data from the Obama Administration. Notably, Richardson and I asked respondents: “Thinking about the personnel in [your agency], in general how responsive are these different groups to the policy decisions of the President?”

Figure 3: Perceived Responsiveness to Presidential Decisions

Both Democratic and Republican respondents reported that senior civil servants are relatively responsive. Seventy-seven percent reported that senior civil servants in their agency are responsive or very responsive to the President. This number is reasonably high, given that some agencies are designed to be unresponsive to the President, such as the Internal Revenue Service and the Federal Reserve System. Because agencies are also constitutionally obligated to be responsive to the law, Congress, and courts, it is unclear how responsive agencies should be to the President.

Importantly, if we disaggregate the data into the most liberal and most conservative agencies, some differences emerge. In the most liberal agencies (i.e., the bottom quartile) close to 82 percent report that senior civil servants are responsive or very responsive to the President. In the most conservative agencies (i.e., top quartile), 74 percent report that senior civil servants are responsive or very responsive to the President. This is a statistically significant difference. In the Obama Administration, then, the vast majority of government executives reported that senior civil servants are relatively responsive to the President. Civil servants in the most liberal agencies reported that their colleagues are marginally more responsive to the President than those in the most conservative agencies. It is natural to assume that the opposite is true for the Trump Administration.

So, is there a vast deep state conspiracy? Based upon what we know about the top levels of the civil service from the last Administration, it is unlikely. Are there pockets of resistance to the new President in some agencies? Probably. This is the case for all new Presidents, Republican or Democrat, and it is presumably due to both statutory responsibilities and the views of civil servants themselves.

What is the proper response in a democratic society? Most previous Presidents have used their authority to make appointments to provide policy leadership across the executive establishment. This maintains the important appearance of neutrality in the civil service by limiting the degree of policy choice exercised by career officials. Limiting the direct policy choices of career executives benefits Presidents from both parties in the long run since it allows elected officials more policy influence and it preserves a competent and neutral administrative apparatus by keeping civil servants out of political fights.

This essay is part of a nine-part series, entitled Valuing Professional Government.

Source for Figures 1 and 2: Survey on the Future of Government Service, 2014.