The U.S. does not regulate more than its international peers, but could still learn much from them about regulatory management.

It is often said that academics could do a better job speaking to the general public. It can probably also be said that academics could use a dose of looking at the forest as well as the trees. In the area of regulatory management, both appear to be true.

In conducting research for a Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) report assessing the federal regulatory system, I noticed that public discourse often overlooks academic research about regulations’ ambiguous effects on the economy and the relatively low regulatory burden on U.S. businesses compared to business in other advanced economies. But by the same token, the academic community could take a step back from the details to look at the long-term U.S. regulation reform record, which is one of stagnation, and compare it with peer countries, which is now not as favorable as it once was.

The general public could be forgiven if they believe that U.S. businesses are being buried under reams of “job-killing” regulations, putting companies at a competitive disadvantage – after all, this is what Republican politicians and many Washington think tanks have been telling the public.

Academic research suggests this is largely bunk. Economists haven’t even figured out how to measure regulatory burden; the best efforts to date rely on crude proxies like counting paperwork hours or the number of pages and restrictive words like “should” and “must” in the Federal Register. We don’t know how the cumulative set of regulations impacts the average company.

As Cary Coglianese and his colleagues have argued, what evidence exists points to employment effects that are generally small and usually localized. As much as former Texas governor Rick Perry likes to claim Texas has a fast-growing economy because it has fewer regulations, the truth is that wealthier states have more regulations, and it’s probably because richer communities demand them. Some of the most costly regulations, such as the Clean Air Act, which vastly improved American’s health, also carry the greatest benefits.

Survey data show that regulatory burden does not put U.S. business at a competitive disadvantage. The United States has long had a less regulated economy than its peers. The U.S. has come in first place among G7 countries in the World Bank’s annual Ease of Doing Business survey in all years but one since the survey began in 2001.

Opinion polls do show a growing divide between Republicans and Democrats on the question of whether the United States is over-regulated, but the polls also suggest that Americans are actually positive about most regulations when pressed on specifics. Although Republican voters and small-business owners say there is too much regulation generally, few can identify individual regulations they want repealed. In a 2012 Pew Research Center survey, the vast majority of Americans, and a clear majority of Republicans, either favored current levels or wanted more regulation for environmental protection, car safety and fuel efficiency, and workplace safety. Survey results were the same twenty years ago, suggesting public opinion has been remarkably consistent and approving of specific federal regulations.

Academic discourse, for its part, could do more to look at the larger picture and what other countries may be doing better than the United States.

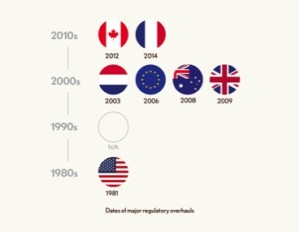

The U.S. was once the trailblazer in regulatory management quality and the gold-standard model for the rest of the world. It was the first country to mandate environmental impact assessments (in 1969), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency developed some of the original cost-benefit analytical methods. The United States was the first nation to set up a dedicated regulatory oversight body – the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) – and to institutionalize cost-benefit analysis and make paperwork reduction an explicit goal. But the fundamental architecture of the U.S. system has not changed in nearly thirty-five years. This fact, along with international comparisons, is rarely brought up in the academic literature.

Over the last several decades, most other rich countries have been busy modernizing their regulatory systems. Countries like Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom can now lay claim to being at the cutting edge of regulatory management. They have implemented systems that better manage and update existing stock, for example, with regulatory budgets and automatic reviews, while also improving the filter for new regulations through empirical study. Australia uses an especially smart approach; instead of siloing retrospective reviews within individual government agencies, its regulatory body periodically does “stockade” reviews of the cumulative set of regulations that affect a given industry, which is how businesses actually experience the regulatory system.

Over the last several decades, most other rich countries have been busy modernizing their regulatory systems. Countries like Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom can now lay claim to being at the cutting edge of regulatory management. They have implemented systems that better manage and update existing stock, for example, with regulatory budgets and automatic reviews, while also improving the filter for new regulations through empirical study. Australia uses an especially smart approach; instead of siloing retrospective reviews within individual government agencies, its regulatory body periodically does “stockade” reviews of the cumulative set of regulations that affect a given industry, which is how businesses actually experience the regulatory system.

The United States would also be wise to learn from the European Union’s use of proportionate analysis that uses back-of-the-envelope calculations for minor regulations and scales up the analytical rigor with bigger regulations. Right now, only massive U.S. regulations get any substantial analysis at all. And in the EU system, bills get a cost-benefit shakedown before parliament votes on them, while it’s the reverse in the United States.

Smarter regulatory management does not have to be partisan. The three trailblazing English-speaking countries currently have conservative governments that are more inclined to limit government reach, but even Socialist-run France plans to adopt a regulatory budget beginning this year. A handful of other European governments are exploring the option. Many of these ideas originated in the United States in the Democratic administration of Jimmy Carter. He set up OIRA and wanted to require built-in retrospective evaluation plans for all new regulations. The Carter-appointed first head of OIRA in 1980 floated the possibility of establishing a regulatory budget. Every president since has conducted regulatory management in the same way, with the same pledges to cut back on waste and lower regulatory burdens, without so much as making a dent in the steady accumulation of paperwork hours and Federal Register pages. No president, Democrat or Republican, has managed to improve U.S. regulatory management.

This is not to say that the United States should implement a strict regulatory budget. A more modest paperwork budget, like Sam Batkins recommends, might make more sense. But clearly there is room for political agreement on how to be smarter about regulations like our peers abroad are – more methodical and institutional retrospective reviews, more empirical scrutiny, and more proportionate analysis. And if public discourse had a clearer-headed understanding of what academics know about regulatory burden, the prospects for regulatory reform might be better and less political.