Coronavirus immunity certificates could permit recovered persons to escape lockdown restrictions.

The International Monetary Fund predicts that the current coronavirus-induced economic downturn could be the worst since the Great Depression. In an attempt to slow the disease’s spread, as much as a third of people globally now live under some form of lockdown restriction.

But what about people who have contracted COVID-19 and recovered?

Policymakers and scholars are considering the possibility of creating immunity certificate programs. These programs would exempt people who have recovered from COVID-19 from societal restrictions, such as limits on public gatherings and operating businesses. Allowing previously infected individuals to return to normal activities might help facilitate efforts to reopen economies while minimizing virus transmission at work.

Governments have required proof of immunity for school attendance, health care employment, and certain travel. But in nations considering immunity certification for COVID-19, government health agencies are discussing programs on a level that appears unprecedented.

Chile introduced the first such national system when the Ministry of Health’s Jaime Mañalich announced recently that Chileans may apply for immunity certificates. To qualify, applicants must demonstrate a positive test result for COVID-19 antibodies and be symptom-free for at least two weeks. Mañalich reportedly has since reframed the certificates as “release certificates” rather than technical certifications of immunity.

China took another approach to granting different freedoms based on COVID-19 status. In contrast to the immunity certificate model, China’s system instead restricts free movement supposedly by predicting an individual’s risk for spreading COVID-19 through an undisclosed algorithm. In partnership with Alipay, Chinese officials mandated a system in which a person’s cell phone app displays colored symbols—green for unrestricted movement, yellow for home isolation, and red for confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis and quarantine. Authorities then check phones before allowing people into public spaces.

In the United Kingdom, the Department of Health and Social Care’s Matt Hancock reportedly claimed that his government is considering immunity certificates, possibly taking the form of a wristband.

In Spain, the Government of Catalonia’s Quim Torra reportedly stated that Catalan authorities are studying possible immunity certificate programs.

In Germany, an epidemiologist coordinating a large study on immunity after COVID-19 infection has reportedly proposed that immunity certificates could permit recovered individuals to work again.

American officials have also raised this idea. Senator Bill Cassidy (R-La.) reportedly suggested creating an online registry to track individuals potentially immune to COVID-19 and permitting them to work. In addition, in response to questions from the press, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, acknowledged that the possibility of immunity certificates “is being discussed” and could “have some merit under certain circumstances.”

The appeal of immunity certificates grows as forecasters predict a protracted recovery occurring over years rather than months. For example, researchers from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health assert that, depending on what interventions the United States takes, the nation may need some form of social distancing measures through 2022. Daily death counts in Italy and Spain suggest that, although containment measures are easing the crisis, the pandemic may recede slowly.

Ongoing studies indicate that many COVID-19 cases could be asymptomatic. In one study, Icelandic researchers observed that 43 percent of the individuals who tested positive for COVID-19 self-reported no symptoms during the study.

Other researchers found that the proportion of asymptomatic cases among COVID-19-positive persons may range from 5 percent to 80 percent. Although the true incidence of asymptomatic individuals may remain unknown for some time, immunity certificates could allow such people to return to work who would otherwise isolate for the potentially unwarranted concern of catching coronavirus.

But immunity certificate programs also raise questions. For these programs to succeed at scale, the antibody tests on which they would rely must be widely available and highly accurate. According to Scott Becker of the Association of Public Health Laboratories, however, many of the available tests reportedly are of “dubious quality.”

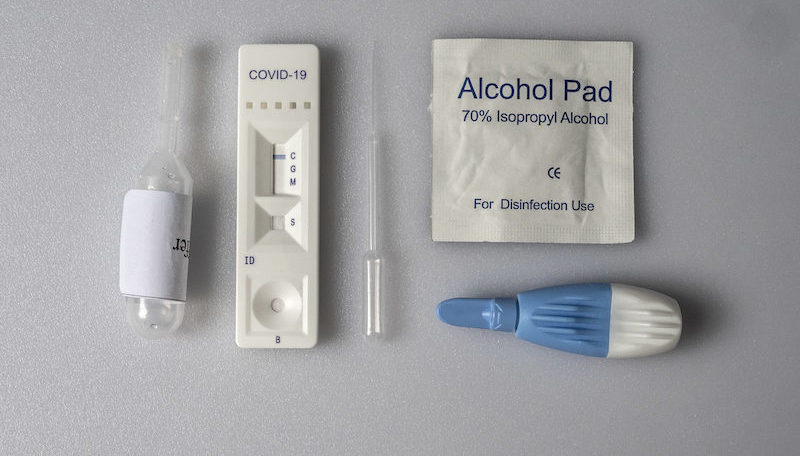

Antibody testing detects proteins that humans generate in response to infections like COVID-19, as opposed to polymerase chain reaction tests, which detect viral particles and assess active infection. Antibodies can remain in the body after an infection, which means that antibody tests should determine who has been exposed to COVID-19 already.

Yet, these antibody tests reportedly yield false positives—results indicating that an individual recovered from COVID-19 when actually that person has not had the disease. False positive rates with COVID-19 tests may be high enough to warrant concern.

A test’s positive predictive value—“the percentage of patients with a positive test who actually have the disease”—describes the likelihood that a positive result confirms infection. Whether a positive result truly confirms infection depends not only on the test’s accuracy but also the disease’s prevalence in the population. In a population with a low disease prevalence, false positives can far exceed true positives due to the sheer number of truly negative individuals tested.

Unfortunately, COVID-19’s prevalence is unclear. Estimates of confirmed cases vary over 40 times across U.S. jurisdictions. Worldwide, confirmed cases per million people reportedly vary over 100 times across countries.

Limited testing capacity and the challenges of tracking a quickly changing target complicate efforts to estimate COVID-19’s true prevalence. With variability in both antibody test quality and disease prevalence assessments, antibody tests may not currently prove reliable enough to justify immunity certificates.

Administrative challenges also abound. In the United States, Fauci reportedly claimed that many antibody test kits will be available, but manufacturing shortages could delay their arrival. Even if antibody test accuracies improve, it remains unclear how quickly government could deploy such testing.

Furthermore, immunity certificates assume that COVID-19 infection does indeed confer immunity. But scientists do not know for certain yet whether such immunity exists. In South Korea and China, some patients reportedly tested positive after recovery, although whether these results reflect reactivation, reinfection, or testing error is unclear. The World Health Organization warns that “there is not enough evidence about the effectiveness of antibody-mediated immunity to guarantee the accuracy of an ‘immunity passport.’”

Moreover, COVID-19 could mutate, potentially creating a sufficiently different strain such that immunity to the current version would not protect against the mutated one.

Some journalists worry that immunity certificates could create a two-tier society. People without certificates could have incentives to commit fraud and misrepresent themselves as immune to acquire restriction exemptions. The availability of immunity certificates could also create “perverse incentives for people to try to contract” COVID-19, potentially further straining burdened health care systems.

Privacy advocates, already concerned with data gathering connected to COVID-19, also highlight the challenges in verifying an immunity certificate holder’s identity through biometric measures and securing new databases with sensitive patient information. Senator Cassidy reportedly describes his proposed system as HIPAA-compliant and respectful of privacy.

One biologist proposes the development of a “CoronaCorps” through which certified-recovered individuals could help the public recovery by delivering supplies to COVID-19 at-risk populations or providing childcare services for health care providers.

Ultimately, as immunity certificate programs seem to promise a pathway to a return to normalcy, they also raise many concerns. Policymakers will need to pay close attention to the specific features of any immunity certificate proposal and keep abreast of ever-developing scientific knowledge about the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.